Sayed Mohammad Firozi 1

1Fellow of Academy in Exile, TU Dortmund University, Germany

*Corresponding Author Email: sayedmohammadfirozi@yahoo.com …

Highlights

- Examines causes of Afghanistan’s first failed modernization during the Amani period.

- Uses discourse analysis of 1921 Constitution, decrees, and reform proclamations.

- Identifies traditional authority, cultural unpreparedness, and foreign-imposed reforms as key obstacles.

- Highlights dissatisfaction among elites and neglect of reference groups in reform efforts.

Abstract

Afghanistan is a country that has taken significant steps toward modernization twice, but each time it has faced serious failures. These failures are closely linked to the current crises in the country. The first failure dates back to the Amani period when the clergy and religious groups rebelled against the modernization efforts of that era. The second failure occurred with the reestablishment of Taliban rule after two decades of international community presence. This paper aims to explore the causes of the first failure in Afghanistan’s modernization process. This study employs discourse analysis with an explanatory-analytical approach. As a qualitative method, discourse analysis is used to uncover the underlying meanings in texts and speeches, focusing on cultural, social, and political contexts. The study population consists of primary sources such as the 1921 Constitution, governmental decrees, and King Amanullah’s reform proclamations, as well as secondary sources, including analytical articles and books discussing the confrontation between tradition and modernity. Purposeful sampling was conducted based on key terms, and after coding the data, discursive signifiers were identified and analyzed. The validity and reliability of this analysis were confirmed using the Potter and Wetherell method to ensure coherence and consistency among the units and discursive signifiers. The findings indicate that the fall and failure of the first modernization process in Afghanistan were due to the influence and authority of traditional structures, the lack of cultural preparation for modernization, the imposition of foreign cultural elements, the exogenous and hasty nature of cultural change (Examples include mandatory unveiling, prohibition of polygamy, compulsory education for girls, and similar reforms.), the neglect of reference groups, and the dissatisfaction of powerful figures with the modernization process.

Keywords: Renovation, Traditionalism, Discourse analysis, Shah Amanullah Khan, Afghanistan.

1. Introduction

Modernism, modernization, the pursuit of modernity, and the aspiration for a modern way of life have been common goals for many developing nations. Among the Third World countries, Afghanistan made two significant attempts toward modernization in the last century, both of which ended unsuccessfully. The first attempt occurred during the reign of Amir Amanullah Khan from 1919 to 1929. Following Afghanistan’s independence in 1919, Amanullah initiated political and economic reforms with a revolutionary zeal. A notable early measure was the establishment of the Louye Jirga (Council of Elders), aimed at amplifying public voices and demands. He also introduced the country’s first constitution, enshrining principles such as the separation of powers, rule of law, civil liberties, and equality of citizens. These principles marked a transformative moment in Afghan history. His reforms also targeted reducing royal authority, reorganizing governmental and military structures, advancing education, and implementing economic changes. Cultural renovation gained momentum after his 1927 European tour, where he encountered modernist ideas. However, these sweeping reforms, implemented with a revolutionary approach, faced significant societal resistance and ultimately led to Amanullah’s abdication (Jalali, 2024).

The second phase of modernization, starting in 2001 with international support, also ended abruptly in 2021. Despite promising progress and opportunities for societal reform, this period culminated in the collapse of the internationally-backed government following a U.S.-Taliban agreement, reversing all achievements overnight (Amani, 2019) . Amanullah Khan’s reform agenda included measures such as abolishing slavery and forced labor, curtailing the privileges of traditional elites, establishing schools, mandating education, and constructing key infrastructure like highways, hospitals, and factories. These initiatives, aimed at modernizing Afghanistan, encountered fierce opposition from traditional power structures, tribal leaders, and clerics, leading to widespread unrest. As a result, the modernization discourse of the period was deemed a failure, forcing Amanullah to abdicate. Scholars have analyzed the reasons for this outcome extensively (Mohib, 2024).

Pamirzad (2024), through an analysis of 80 issues of Aman-e-Afghan, the official publication of Amanullah Khan’s government (1919–1929), revealed that this publication, following the policy trajectory of Siraj-ul-Akhbar, advocated for pan-Islamism, nationalism, and modernism. The pan-Islamism promoted by this publication emphasized Muslim unity, inspired by the struggles of Muslim countries under colonial rule. Nationalism, on the other hand, aimed to foster a cohesive nation, albeit with ethnocentric tendencies. The publication also sought to reconcile tradition with modernity by emphasizing education, lawfulness, and legislation as tools to guide Afghanistan toward modernization. However, the inherent contradictions in these values prevented the successful integration of tradition and modernity. Eslami and Rahimi (2024) argue that the reign of Amanullah Khan (1919–1929) witnessed a profound clash between tradition and modernity in Afghanistan. Amanullah’s modernist efforts, including constitutional reforms, educational initiatives, press freedom, and women’s rights, faced strong societal resistance. This resistance stemmed from the neglect of national and religious values, superficial imitation of Western models, and the hasty implementation of reforms. The lack of effective dialogue between traditionalists and modernists deepened societal divisions, ultimately leading to the failure of reforms, the collapse of Amanullah Khan’s government, and the long-term suspension of modernization and constitutional discourse in Afghanistan. Monib (2024) highlights Amanullah Khan’s significant role in Afghanistan’s modernization, from achieving national independence to implementing modern reforms and policies. However, the study notes that Amanullah’s own actions eventually undermined his progress, leaving a dual legacy of advancement and failure. Andishmand (2014) attributes the failure to factors such as reducing modern values to ethnic nationalism and neglecting the sociocultural preconditions for reform. Rasouli (2017) emphasizes the role of haste, disregard for tribal traditions, and foreign interference.

In summary, the primary reasons for the failure of Amanullah’s reforms are grouped into internal resistance from traditional structures and external colonial interventions. This research delves deeper into the interplay between tradition and modernity during Amanullah’s modernization efforts, using a sociological lens to examine the sociocultural dynamics. By employing discourse analysis, this study identifies central and discourse markers, tracing the interconnectedness of ideas and resistance within the modernization narrative. Through this approach, it reconstructs the sociocultural atmosphere of the Amani period, providing readers and reformists with nuanced insights into the factors behind the failure of Afghanistan’s early modernization attempts

1.1 Objectives

The primary objective of this research is to identify the sociological factors behind the failure of the first modernization process in Afghanistan. To achieve this, the study addresses the following questions:

- Why did the modernization discourse in Afghanistan fail?

- What were the social and cultural factors contributing to this failure?

- How did traditional and conservative structures oppose the modernization discourse?

- What challenges and weaknesses undermined the modernization discourse?

- How did reference groups react against the reformative efforts?

- What were the main responses to the modernization attempts?

1.2 Conceptual framework

Culture encompasses various aspects, elements, features, and levels. Undoubtedly, culture is a concept with diverse meanings and cannot be comprehensively defined. However, according to a simplified definition, culture is considered a complex set of knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, ethics, habits, and everything a person learns from their society (Côté, 2023).

Sociologists argue that culture, being dynamic, possesses both permanence and stability. In other words, the culture of a society does not change in a revolutionary or immediate manner; instead, cultural reforms occur gradually and continuously. The imposition of external cultural reforms, the introduction of alien cultural elements, and the acceleration or revolutionizing of culture can lead society toward anomie, abnormality, and internal resistance. Anthropologists define culture as the lifestyle or way of life that people have collectively accepted over time. This lifestyle evolves into a collective identity, making it difficult, if not impossible, to change without resistance (Lash, 2013).

Moreover, social science experts emphasize that imposing reforms from the top down, coupled with resistance from the bottom up, places society at a critical juncture where it must either adapt to survive or risk fading away. According to Talcott Parsons’ functional-structural theory, which focuses on the survival and continuity of systems, four tasks are essential for any system to ensure its longevity:

a) Adaptation: A system must adapt to its environment. Its survival depends on understanding and responding to environmental conditions.

b) Achievement of goals: A system must define and achieve its primary objectives. Failure to set logical and legitimate goals or to realize them endangers the system’s existence.

c) Integration: A system must regulate the interrelationships among its components. A lack of such regulation leads to functional crises within the system.

d) Pattern maintenance: A system must create, sustain, and renew both the motivations of individuals and the cultural patterns that foster these motivations. This ensures cultural order and symbolic understanding (De Velazco et al., 2021).

However, during Afghanistan’s first attempt at renovation and modernization (1919–1929), the incumbent system failed to meet these functional-structural tasks necessary for survival. This failure placed Afghan society on a path toward anomie at a crucial historical juncture. From a theoretical perspective, there are at least two significant and well-known schools of thought regarding pathways to development and renovation. According to the first school, the most effective model for renovation and development is that of Western developed countries. The early theorists of this school considered it the sole viable model, while later proponents recognized the value of internal patterns with minor adjustments. In this context, dependency theory advocates for non-compliance or even disconnection from Western developed countries. More recent theories within this school do not entirely reject assistance or the adoption of certain Western practices (So, 2018). Samir Amin, a prominent theorist of the dependency school, suggests that self-centered development or disconnection is the key to overcoming dependency (De Velazco et al., 2021). From this perspective, dependency is not voluntary; rather, it is a structural phenomenon where dependency and underdevelopment are interrelated and mutually reinforcing (So, 2018).

2. Material and Methods

This research is developmental in terms of goal and documentary in terms of sources. The research method is discourse analysis with an explanatory-analytical approach. Generally, discourse analysis serves as a method of studying texts, media, cultures, sciences, politics, societies, and the like.

Specifically, it is a qualitative research method used to discover the meaning in a text or speech in various social, cultural, and political contexts (Kalantar et al., 2009). The analysis of discourse in writing and speech is conducted by the careful pragmatic evaluation of the language considering the place and time conditions. That is, understanding the atmosphere in which a piece of communication occurs helps to find out about the people involved and the whys and wherefores of their propositions, instead of communicating directly with them (Ibtikari, & Esai Khosh, 2017).

Discourse analysis, in its broadest sense, is the study of a society through the analysis of the samples of its language, including face-to-face conversation, written media texts, documents, images, and symbols. Studies in this field are based on a wide range of theories and analytical approaches to investigate the meaning. They focus on the cultural, social, and political contexts in which texts and conversations are created (Koteyko & Atanasova, 1996).

The present study focuses on the atmosphere of confrontation between renovation and traditionalism in the Afghan society under Shah Amanullah. The documents analyzed in this regard were the available first-hand sources including the first Constitution of Afghanistan as the code of ruling ordered by Shah Amanullah and ratified in Paghman Louye Jargah (i.e., meeting of elders) in 1921, the penal code, the resolution of Paghman Louye Jargah signed by a thousand members in 1928, executive orders, and official announcements such as those to allow hijab removal and determine men’s clothing. These sources and documents served as a framework to adopt policies for renovation and reforms at that time. As for the second-hand sources, this study benefited from some books and papers on the contrast between tradition and modernity and the failure in the first renovation process in Afghanistan. These sources were also cited in the literature review. The sampling was conducted with keywords and tables of contents in a purposeful way. The steps of the analysis were determined after the research questions were set. Then, the data collection, processing and coding were carried out. Finally, the discourse markers were extracted, classified and analyzed. The validity and the reliability of the analysis were evaluated by the Potter and Trowel method, in which the coherence and coordination of different parts of a text and the corresponding markers are viewed as the elements that shape up the discourse (Ibtikari, & Esai Khosh, 2017).

3. Results & Discussion

3.1 Structural renovation and traditional elements resistance

Afghanistan is recognized as a country with a deeply rooted religious and ethnic structure (Sajadi, 2001). Ethnicity and religion are two pivotal variables shaping social relationships and playing a significant role in determining the fate of its people. The Amani period, considered the first phase of modernism in Afghanistan, was characterized by strong and influential social structures, including traditions, religion, tribal ties, the presence of khans and lords, and elements of Afghan nationalism (Rasouli, 2017). For example, in the Loya Jirga (Council of Elders) held in Nangarhar in 1923 and the Loya Jirga of Paghman in 1924, the vast majority of participants were religious scholars and tribal and ethnic elders (Jalali, 2024). Concurrently, speeches delivered by the young king before his historic trips to European and Asian countries demonstrate his deep belief in the religious values and social traditions of Afghan society at the time (Eslami and Rahimi, 2024). The dominant social structures of the era included strong traditional, religious, and tribal elements. As a result, an overnight transformation in the lifestyle and culture of society was implausible due to such rigid, fundamentalist, and traditional frameworks. The overarching societal structure and the entrenched mindset of the people were not amenable to rapid change. Consequently, the reforms and modernization efforts provoked widespread anger and resistance from the population.

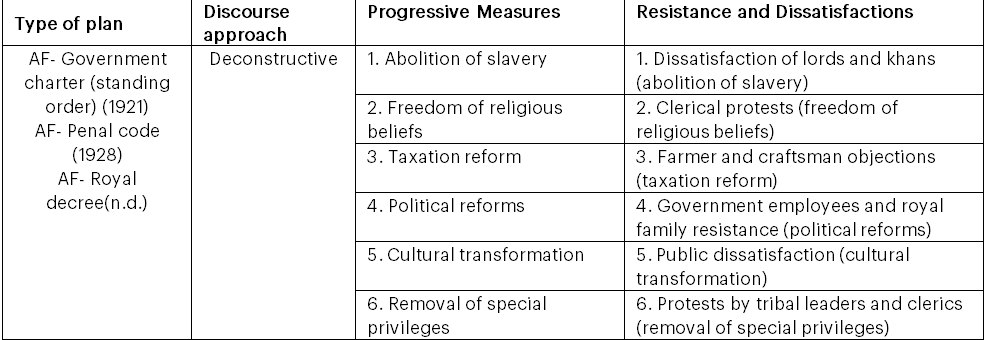

Table 1: A summary of the structural renovation discourse, discourse approach, and its markers

Moreover, Afghanistan had an undeclared opposition to western culture and values after the Afghan and British wars when the country sensed the good taste of freedom. Some believe that, after the historic trips in 1927-1928, the young king attributed the backwardness and underdevelopment of the Afghan society to the cultural-religious attitudes of the people. According to Muhyiddin Anis, in the Jargah of 1928, decisions were made on disuniting and scorning clerics (Rasouli, 2017). All this indicates that Shah Amanullah Khan, the modernist king of Afghanistan, did not have a correct understanding of the status and power of the ruling social structures. As demonstrated by the discursive signifiers in Table (4-1), the modernization discourse during King Amanullah Khan’s era largely disregarded the powerful social structures and traditions of Afghanistan, striving for their abrupt and revolutionary elimination. The abolition of slavery, as one of King Amanullah’s foundational decisions, aimed to dismantle class-based and unjust systems. This measure, which was part of a justice-oriented and anti-traditional discourse, directly threatened the economic and social interests of tribal leaders and local elites. These groups, possessing substantial economic power and social influence within the tribal framework, perceived the reforms as a challenge to their status and resisted them vehemently.

On another front, the discourse of religious freedom, a key element of the reform agenda, sought to liberate religion from the exclusive control of the clergy and to grant individuals greater freedom in their beliefs and religious practices. This initiative, however, led the clergy to feel that their historical influence and unique position in society were being undermined. Their dissatisfaction and opposition highlighted their strong resistance to modernization and social changes. Furthermore, the abolition of privileges enjoyed by the clergy and tribal leaders weakened their societal standing. This measure, rooted in the discourse of equality, provoked intense opposition from these groups, reflecting their effort to maintain traditional authority and resist emerging discursive changes

In the economic sphere, tax system reforms aimed at increasing transparency and economic justice led to discontent among farmers and artisans. These groups, accustomed to traditional tax structures, viewed the new changes as a threat to their livelihoods and opposed them. Although the economic modernization efforts aligned more closely with principles of justice, they ultimately resulted in conflicts of interest with the productive sectors of society. Politically, reforms such as mandatory military service, the restriction of royal family privileges, and administrative restructuring sought to replace hereditary and centralized systems with a more transparent and democratic governance structure. These changes jeopardized the interests of traditional power groups, causing dissatisfaction and resistance among government employees and members of the royal family. These discursive signifiers reveal attempts to break the monopoly of power, but in practice, they culminated in a clash between tradition and modernity. Culturally, modernization reforms, including changes in dress codes, education, and social behaviors, generated widespread dissatisfaction among the general populace. These reforms, promoted as part of the modernization discourse, contradicted the traditional values and beliefs of society. Consequently, many individuals perceived these changes as a threat to their cultural and social identity.

The analysis of the discursive signifiers in the above table demonstrates that King Amanullah Khan’s attempts at modernizing Afghanistan, contrary to the country’s social and cultural foundations, were implemented without adequately considering the role of traditional powers and social sensitivities. Each of these signifiers represents the inherent tension between the discourses of modernity and tradition. The mismatch between the reform initiatives and the societal context ultimately led to widespread resistance and the failure of these efforts. These findings underscore the critical importance of a thorough understanding of social realities and aligning reform discourses with existing structures for the success of any reform agenda.

3.2 Lack of Acculturalization and Imposition of Cultural Elements

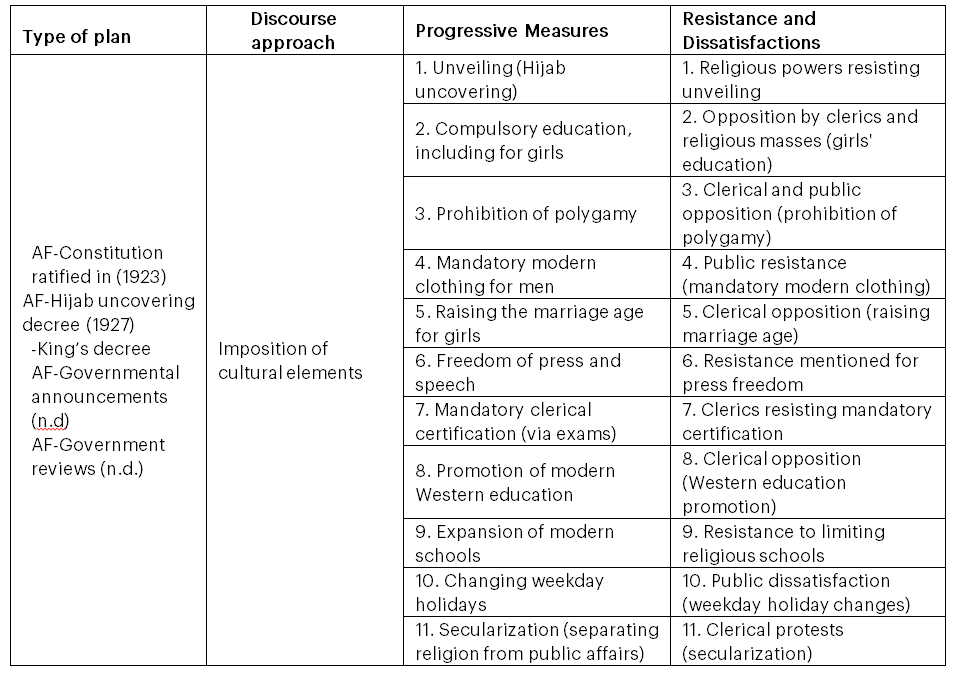

Table 2: A summary of cultural renovation plans, discourse approach, and its markers

The findings of Table 2 highlight King Amanullah Khan’s efforts in the 1920s to modernize Afghanistan through cultural and social reforms. These reforms, often implemented in a top-down and compulsory manner, faced widespread resistance as many of them clashed with the traditional and religious values of Afghan society. A detailed analysis of these reforms, supported by credible sources, is provided subsequently. The Constitution of 1922 (1301 AH) was drafted to institutionalize modern governance by replacing customary and religious laws with secular ones. Although aimed at promoting justice and equality, it was perceived as a threat to religious authority and tribal structures, prompting resistance from clerics and tribal leaders.

The decree on unveiling (Kashf-e-Hijab) was among the most controversial reforms. Issued with the goal of liberating women and promoting social progress, it stood in stark opposition to the deeply ingrained religious and cultural norms of society. Religious scholars and the public viewed this measure as an assault on Islamic hijab, resulting in severe opposition. Additionally, the publication of Queen Soraya’s photographs in Western attire became a tool for opponents to portray the king as irreligious (Rasouli, 2017). Educational reforms, particularly the education of girls, also faced strong backlash. Co-educational and compulsory schooling were perceived as Western interference in cultural affairs and were declared forbidden by clerics. These reactions polarized society in response to the reforms. The prohibition of polygamy was another reform that directly contradicted Islamic rulings. This measure was viewed by religious scholars and traditional communities as a violation of sacred and religious rights, leading to widespread protests. The imposition of Western attire for men, including suits and the “chapeau” hat, was seen as an attempt to enforce Western identity on Afghan society. Many men opposed shaving their beards and adopting Western clothing, considering it a betrayal of Islamic and cultural values.

The reforms also aimed to improve women’s rights and reduce child marriages, but religious scholars and traditionalists interpreted these measures as an attack on Islamic marriage laws and reacted strongly against them. Similarly, freedom of the press and thought, although intended to modernize social discourse, was perceived as a threat to the monopoly of religious scholars over the interpretation of religious matters. These freedoms provoked negative reactions from clerics and widespread opposition to the reforms. Introducing tests for clerics and expanding secular education in schools were viewed as serious threats to the traditional system of religious schools. Clerics regarded these reforms as attempts to diminish religious influence and replace it with Western education.

Reforms concerning official holidays and the separation of religion from public affairs deeply provoked clerics and traditionalists. These measures were interpreted as efforts to secularize Afghanistan’s Islamic society. Overall, King Amanullah Khan’s attempts to modernize Afghanistan, despite their positive intentions and progressive goals, ultimately failed due to their coercive nature, misalignment with societal traditions, and disregard for cultural and religious sensitivities. These actions not only eroded public trust in the government but also provided internal and external opposition with opportunities to mobilize against the king’s ref

3.3 Exogenousness of the Renovation Plans and their Hasty Implementation

Shah Amanullah Khan’s cultural modernism did not have acceptable grounds and was practiced in the absence of the necessary socio-cultural infrastructures. Reformation through changing the people’s lifestyle and making the imitation of Western culture compulsory induced the resistance of the people and the clergy. Strong conflicts between old and new cultural elements, one from top down and the other from bottom up, caused a wave of unrest and anomie. The society’s getting anomic and the public dissatisfaction with the cultural renovation and the imposed cultural elements are known as the factors leading to the failure of the renovation process at that time.

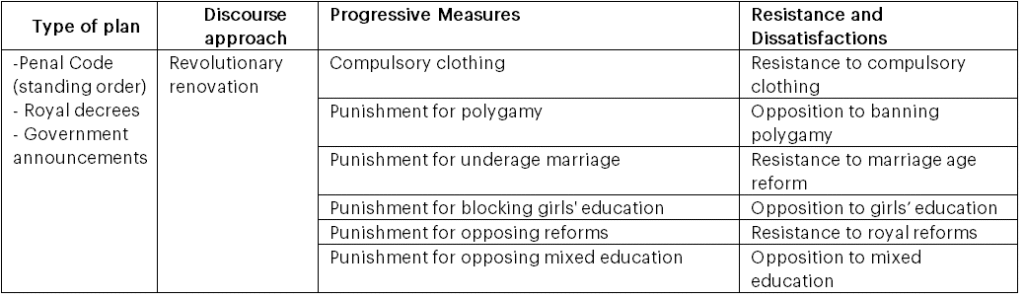

Table 3: Summary of forceful and revolutionary renovation discourse markers

The findings presented in Table 3 highlight the adoption of a revolutionary and coercive modernization approach during the reform era of King Amanullah Khan. According to this table, tools such as the Penal Code, royal decrees, and governmental proclamations were employed as discursive mechanisms to advance the reforms. This approach emphasized punishment and sanctions against opponents of the reforms as the central discursive nodes. For instance, individuals who failed to adhere to the mandated dress code faced official penalties. This policy, aimed at imposing Western attire on society, provoked widespread negative reactions among the populace and religious leaders.

Similarly, penalties were imposed on individuals who practiced polygamy. This law, perceived as conflicting with Islamic principles and traditional customs, triggered significant opposition from conservative groups. Another example was the punishment of individuals who married girls under the age of 18. While this measure sought to reduce child marriages, it was criticized by many clerics as an intrusion into Islamic laws. Moreover, individuals who hindered girls’ education faced penalties. Although this policy aimed to promote female education, it encountered strong resistance from traditionalists.

Additionally, sanctions were enforced on all opponents of the royal reforms, creating an atmosphere of repression and curtailing any organized resistance. Opponents of co-education for boys and girls also faced penalties, a policy that attracted severe criticism from religious scholars and conservative segments of society, further polarizing the community.

In summary, King Amanullah Khan employed coercive and mandatory measures to implement his reforms. Although ostensibly designed to promote modernization, this approach ultimately deepened the divide between the government and the people. Religious leaders and tribal elites capitalized on this situation to incite public opposition against the reforms. These measures not only led to widespread uprisings in Kabul and northeastern Afghanistan but also drew influential religious families, such as the Mujaddidis, and major tribes, such as the Shinwaris, into the opposition movement. These uprisings demonstrated that neglecting the interests and influence of key reference groups can trigger intense social and political resistance, ultimately undermining the objectives of modernization.

3.4 Ignoring Reference Groups

In sociology, reference groups are defined as those whose behavior is imitated by other members of society. These groups serve as a benchmark for self-evaluation, allowing individuals to compare themselves to reference groups to assess their success in life. People’s attitudes, decisions, and actions are often shaped by the influence of these groups (Mazinani et al., 2022). Societies identify reference groups based on their specific structure and circumstances. In Afghan society during the Amani period, elders, religious figures, khans, and the heads of ethnic and tribal groups were regarded as reference groups. Shah Amanullah Khan, however, underestimated the influence and interests of these groups. His renovation and reform plans often clashed with their interests. The modernist king failed to reconcile the interests of the reference groups with his reform agenda, ultimately alienating these influential figures. Marginalizing and even disregarding their interests led the reference groups to incite public opposition to the king and his initiatives. Although all of Amanullah’s 64 development and reform plans were designed to benefit the public (Jalali, 2024), the people failed to comprehend the principles and potential effects of these reforms. Instead, they relied on the guidance of the reference groups. The press and media, which aimed to promote the reforms and persuade the public of their benefits, had limited influence. In contrast, the reference groups easily swayed public opinion and mobilized people to act in their favor.

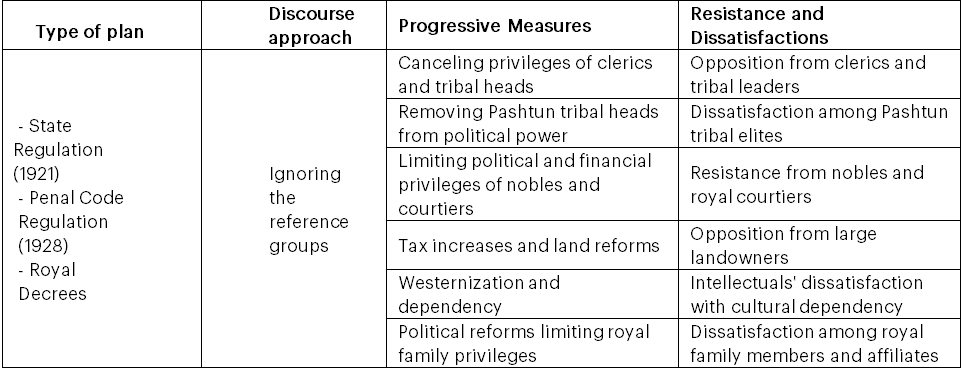

Table 4: Renovation regardless of the reference groups, discourse approach and its markers

The findings presented in Table 4 highlight the adoption of a modernization approach during King Amanullah Khan’s reform era, which disregarded the interests of key reference groups. According to the table, instruments such as the Land Reforms Charter, the 1922 Constitution, tax laws, royal decrees, and speeches were utilized as discursive tools to advance the reform agenda. This approach directly threatened the interests of influential groups such as clerics, tribal leaders, large landowners, nobles, and even some intellectuals. The revocation of privileges for clerics and tribal leaders emerged as a significant discursive element, causing severe dissatisfaction among these groups, as it undermined their socio-economic status. The exclusion of Pashtun tribal leaders, including the Mangal, Shinwari, and Ahmadzai clans, from political power further provoked strong negative reactions, as it was perceived as a direct threat to their influence within the governance structure.

Additionally, the curtailment of financial and political privileges for the aristocracy and courtiers, particularly following political reforms, sparked widespread discontent among these groups. Large landowners, in particular, were adversely affected by increased taxes and land reforms, further exacerbating their grievances. Another consequence of these reforms was the rise of Westernization and dependency, which dissatisfied certain intellectuals. These individuals, who had initially anticipated positive change, grew disillusioned due to the misalignment of reforms with the society’s actual conditions and needs, leading them to distance themselves from the king’s agenda. Moreover, political reforms that restricted the privileges of the royal family also incited dissatisfaction among certain members of the monarchy and the king’s inner circle. Deprived of their influence and power, these individuals opposed the reform programs. Overall, King Amanullah Khan’s reform initiatives were designed and implemented without adequately considering the interests and perspectives of reference groups. This oversight resulted in a convergence of diverse factions opposing the king’s reforms. The widespread uprisings in regions such as the eastern provinces, Paktia, and Khost—led by tribes such as the Ahmadzai, Jaji, and Mangal—serve as examples of these groups’ resistance to King Amanullah Khan’s modernization approach.

3.5 Equivalence Chain of Regressive and Resistant Discourse Markers versus Renovation Discourse Markers

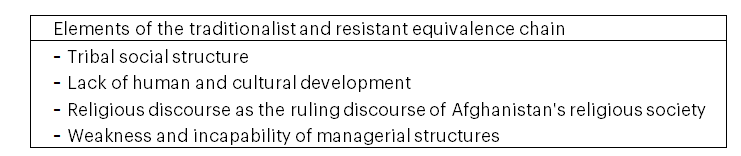

The elements and circles of equivalence are indirectly and non-tangibly supported by the central marker. They eliminate the competing discourse markers and elements to help the markers of the central discourse. As shown in Table (6), there were certain elements and circles that supported the traditionalist and resistant discourse against the renovation discourse.

The first resistance was shown by the tribal and social structures. Since long ago (mid-19th century), when there were several rebellions against the central government, the ethnic groups in Afghanistan had clearly and officially divided into insiders (familiar) and outsiders (strangers). Some of these groups were massacred or forced to migrate and give up their religious beliefs (Mousavi, 1990). From then on, some tribes were traded as slaves, some had fixed government salaries, and some were in between these two situations.

Table 5: Elements of the equivalence chain of traditional and resistant markers versus the renovation discourse markers

The abolition of the slavery of the Hazara people and the abolition of the government privileges for Khans and some tribes, like the other renovation plans, did not match the traditional social structures and fueled anti-government riots.

The second element against the renovation discourse was the lack of human and cultural development. The renovation discourse was imposed on the traditional society in a very serious and hasty manner at the time when the society was not ready to make a move toward human and cultural development. Undoubtedly, such a society would not tolerate an abrupt change or development and considered the king’s renovation plans to be westernized and dominated by the western culture.

Thirdly, there was the religious discourse as the dominant and ruling discourse in the society. The power and influence of religious elements rejected non-religious processes and introduced them as the enemies of both worlds of the nation. The power of the religious discourse to excommunicate did not give the opposing discourse an opportunity to be established or expanded; rather, it helped the regressive and traditionalist discourse.

Fourthly; the managing structures were weak and incapable. The reforms were implemented by a government that was not managerially able to adapt, defend and justify those reforms in the society; even some government officials and intellectuals parted from the renovation plans and discourse.

3.6 The Otherness Discourse of Tradition against Renovation

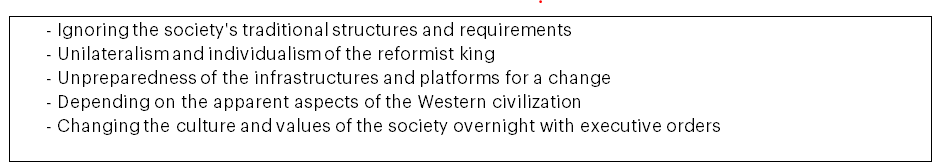

In this study, the otherness issue is a part of the discourse analysis that refers to the neglected markers of the renovation discourse. It has been found that, if these markers were paid attention to, the power and influence of the rival discourse would be reduced, which could contribute to the establishment and durability of the renovation discourse.

Table 6: The otherness markers in the renovation discourse

As it can be seen in Table 6, the king started his renovation plans for the development of Afghanistan with the imagination that he could change the people’s lifestyles, opinions and tradition as well as the society’s structure by executive orders. Such imaginations are considered unrealistic. If the renovation discourse had been gentle, with a respect for the traditional structures and requirements and the reference groups, and had made the intended changes without creating cultural sensitivities, it would have definitely ended differently. In addition, the nature of the renovation discourse at that time was mostly imitative; it just sought to copy the appearances of the Western civilization. Indeed, this approach ignored the historical, structural, cultural and social differences of Afghanistan and the West. All this was attempted with executive orders in a top-down authoritative manner, which fueled the public resistance and contributed to the regression and traditionalism.

3.7 Traditionalist Discourse as a Central Marker

The discourse markers, equivalence chain and otherness markers discussed in this research denote that the traditionalism, or conservatism, of the society was the main factor for the failure of the renovation process. This factor is known as the central marker of the discourse analysis here. The traditional culture and the structural elements of the then-Afghan society were so powerful as to consider any kind of change or innovation as an enemy or an alien value. The people even did not create any opportunity or a context for peaceful negotiation with the renovation discourse, nor could they tolerate the establishment and expansion of the renovation markers.

In such a situation, the reformist king, unaware of the power and influence of tradition, issued new orders every day and did not listen to opposing voices. The durability of this situation gave more cohesion, coincidence and harmony to traditionalists and conservatives, and they organized public revolts one after another. The king and his renovations were excommunicated and alienated by religious and tribal leaders, who had become united against him. This was the beginning of the collapse of the renovation discourse. The power of traditional, religious and tribal elements overcame the king’s modernist plans and actions, and the whole renovation process ended in failure.

4. Conclusion

In Afghanistan’s history, the Amanullah period is regarded as one of the most remarkable and progressive eras for reforms and development. King Amanullah Khan assumed the throne and governmental authority at a time when Afghanistan was deeply entrenched in crises. The country faced a closed and tribal society, a traditional social structure and culture, a lack of modern and effective administrative systems, widespread illiteracy, pervasive poverty, and numerous other challenges.

The young king, who had promised independence and reforms after ascending to power, garnered support from various social groups, leading to his success in reclaiming Afghanistan’s independence. Early in his reign, he initiated political and economic reforms, which initially gained significant public approval. However, following an extended six-month journey to several European and Asian countries in 1927–1928, he intensified his cultural modernization initiatives. This wave of modernization, however, sowed the seeds of his downfall. Notable reforms included lifting the veil for women, beginning with his own wife, banning child marriages, prohibiting polygamy, introducing mixed-gender education and mandatory schooling, adopting Western attire such as suits and hats, sending girls abroad for education, curtailing the authority of religious leaders and tribal chiefs, and removing religious studies from curricula.

The young king viewed cultural transformation as the foundation for broader societal change and thus pursued sweeping cultural reforms without adequately considering structural and cultural barriers. He underestimated—or perhaps overlooked—the influence, power, and reach of traditional and religious structures. Moreover, the modernist king failed to recognize the authority and sway of key societal figures such as religious leaders and tribal chiefs, whose interests he undermined by curtailing their powers. His cultural reforms were criticized for being hasty, externally imposed, and out of sync with Afghanistan’s cultural context.

Other factors, such as his individualistic decision-making, inexperience, arrogance, and inconsistency in governance, compounded these challenges. Economic poverty, alongside British Indian and Soviet interventions aimed at weakening his reforms, also played a role in his failure.

The discourse of modernization ultimately succumbed to the conservative and traditionalist narrative following the collusion of influential groups and widespread uprisings. Nevertheless, the lessons learned from this historical period can inspire innovative strategies for Afghanistan’s future—strategies that take into account the nation’s cultural, social, and economic realities. Such approaches could transform current challenges into opportunities for progressive change, laying the groundwork for overcoming past crises and advancing sustainable development and social justice. Failure to heed the lessons of King Amanullah Khan’s modernization era and similar historical experiences risks trapping the country in a recurring cycle of crises. Such a trajectory would not only squander opportunities for growth and sustainable progress but also leave future generations mired in deeper poverty, instability, and backwardness.

Acknowledgement

Thanks to the officials of the Central Library and National Archives of Afghanistan who provided the necessary documents for this research

Conflicts of Interest

There is no conflict of interest.

References

Afghan Government (AF). (1921). Government charter (Standing order / State regulation) [Government document]. National Archives of Afghanistan.

Afghan Government (AF). (1928). Penal code [Government document]. National Archives of Afghanistan.

Afghan Government (AF). (n.d.). Royal decree [Government document]. National Archives of Afghanistan.

Afghan Government(AF). (1923). Constitution ratified [Government document]. National Archives of Afghanistan.

Afghan Government (AF). (1927). Hijab uncovering decree [Government document]. National Archives of Afghanistan.

Afghan Government (AF). (n.d.). King’s decrees [Government documents]. National Archives of Afghanistan.

Afghan Government (AF). (n.d.). Governmental announcements [Government documents]. National Archives of Afghanistan.

Afghan Government. (n.d.). Government reviews: Aman al-Afghan, Serj al-Akhbar, Ershad al-Neswan Review, Ettehad Mashreqi Review, Ettefaq Islam Review, Bidar [Government periodicals]. Kabul Public Library.

Amani, Z. (2019). The wrong approach to peace-building in Afghanistan (Doctoral dissertation, Department of International Relations, Central European University, Budapest, Hungary).

Andishmand, E. (2014). State-nation-building in Afghanistan. Saeed, Kabul.

Côté, J. F. (2023). Jeffrey Alexander and cultural sociology. John Wiley & Sons.

De Velazco, F. F., Lara, E. C., & Luna, S. R. (2021). Proposal of a model from the perspective of Parsons’ functional-structural theory. Journal of Systemics, Cybernetics and Informatics, 19 (8), 182–197.

Eslami, R., & Rahimi, W. (2024). The antagonistic conflict between tradition and modernity in Afghanistan and the violent outcome (1919–1929). Central Eurasia Studies, 17 (1), 27–52. https://doi.org/10.22059/jcep.2024.372554.450201

Ibtikari, M. H., & Esai Khosh, K. (2017). A study of the theory, method, and application of discourse analysis. Scientific Journal of Research Approaches in the Social Sciences, 2, 64-86.

Jalali, B. (2024). Modernization in Afghanistan: 1905–1973. Historical Yearbook, 21 (XXI), 53–69.

Kalantar. p. Abbaszadeh, M. Saadati, M. Pourmohammad, R. & Mohammadpour. N.(2009). Discourse Analysis: With Emphasis on Critical Discourse as a Method of Qualitative Research, Sociological Quarterly. 1 (4): 7-28.

Koteyko. N &.Atanasova.D.(1996) Discourse analysis approaches for assessing climate change communication and media representations, Oxford Encyclopedia of Climate Change Communication Publisher: Oxford University.

Lash, S. (2013). Sociology of postmodernism. Routledge, New York.

Mazinani, M., Hazrati Sovmee, Z., & Kashani, M. (2022). Sociological study of the effect of reference groups on social capital (Case study: Students of talented high schools in Tehran City in academic). Political Sociology of Iran, 5 (7), 326–346.

Mohib, A. (2024). Nation building in Afghanistan: A failed nation and a collapsed country. Why did Afghans fail to build a nation?

Monib, A. (2024). A historical look at the reforms of Amir Amanullah Khan. Kunduz University International Journal of Islamic Studies and Social Sciences, 149–164.

Mousavi, S. A. (1990). Hazaras of Afghanistan (A. Shefahi, Trans.). Simorgh, Tehran.

Pamirzad, Q. H. (2024). The intersection of pan-Islamism, nationalism, and modernism in Afghanistan’s press in the independence era: A thematic content analysis of Aman-e-Afghan weekly. QAULAN: Journal of Islamic Communication, 5 (1), 86–103.

Rasouli, Y. (2017). Tradition and secularism in Afghanistan. Nabisht.

Sajadi, S. A. (2001). Political sociology of Afghanistan (Ethnicity, religion, and government). Bustan, Qom. So, A. Y. (2018). Social change and development: Modernization, dependency, and global system theories (M. Habibi, Trans.). Research Institute of Strategic Studies, Tehran. (10th ed.).

About this Article

Cite this Article

APA

Firozi, S. M.(2025). A Reflection on the Failure of the First Renovation Process in Afghanistan (A Sociological Analysis of Shah Amanullah Khan’s Failed Modernization Efforts in Afghanistan. SustainE. 1(2). doi:10.55366/suse.v1i2.12. 1-13.

Chicago

Firozi, S. M.(2025). A Reflection on the Failure of the First Renovation Process in Afghanistan (A Sociological Analysis of Shah Amanullah Khan’s Failed Modernization Efforts in Afghanistan.. SustainE. 1, no. 2 (May 20, 2025). 1-13. https://doi.org/10.55366/suse.v1i2.12

Received

15 January 2025

Accepted

23 March 2025

Published

20 May 2025

Corresponding Author Email: sayedmohammadfirozi@yahoo.com

Disclaimer: The opinions and statements expressed in this article are the authors’ sole responsibility and do not necessarily reflect the viewpoints of their affiliated organizations, the publisher, the hosted journal, the editors, or the reviewers. Furthermore, any product evaluated in this article or claims made by its manufacturer are not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Distributed under Creative Commons CC-BY 4.0

Share this article

Use the buttons below to share the article on desired platforms.