REVIEW

Surabhi Srivastava

LL.M. student (2025-26), National Law University, Jodhpur

RESEARCH ARTICLE

This article is part of a special issue titled Bridging Power and Knowledge: Addressing Global Imbalances in Knowledge Systems for Sustainable Futures.

PLAIN-LANGUAGE SUMMARY

Study Focus

Climate change disproportionately affects LGBTQIAP+ communities in the Global South. These groups face a “double burden” from existing discrimination in employment, housing, and healthcare, exacerbating their vulnerability to climate impacts.

Key Challenges & Findings

Implications & Solutions

Current climate policies largely overlook LGBTQIAP+ communities, failing to account for how discrimination intensifies their climate vulnerability.

- Integrate LGBTQIAP+ perspectives into climate planning.

- Ensure emergency shelters are safe and inclusive for all gender identities.

- Improve data collection on climate impacts across diverse communities.

- Hold developed nations accountable for their role in the climate crisis.

WATCH A SUMMARY OF THE ARTICLE

LISTEN TO THE PODCAST

Abstract

The purpose of the present paper is to understand how minorities and vulnerable communities, especially the LGBTQIAP+ in the Global South, are affected by climate change and face the brunt of it. The queer community is discriminated against in cisgender-heteronormative State policies with respect to employment, housing, and healthcare. Such policies result in exclusion from healthy environmental exposure and vulnerability, which is coupled with individual factors of behavioral exclusion, and mental health, causing environmental health disparity in the community, as illustrated in a case study of transgendered persons in India. The trans-community in India has faced societal segregation based upon their sexual identity, and has not been legally recognized as the ‘third gender’ until lately in 2014, leading to exclusion from most socio-economic aspects of life. Mapping the impact of climate change on the trans-community in India presents a categorical analysis of queer-biases in the environmental jurisprudence and policies. Climate change is increasingly a subject of international law and treaty obligations of expedient implications wherein State unity is required to achieve the goals, for all, by all. This paper studies the lacuna of the international environment regime towards the queer community, analyzing the status of their interests in municipal laws and the obligations of States to the international climate regime, studying the same from the third-world perspective and the liabilities of the climate crisis that the developed nations do not recognize and how that affects the queer community. This paper attempts to bring insights into international environment law from the perspective of the vulnerable, recognizing the lack of institutional effort and policy-making towards the cause, while the proportion of queer persons suffering from climate-change-related health issues is higher than other populations. It aims to propose accountability to powerful stakeholders whose decision-making has little to no representation from the queer community. This paper highlights the legal essence of the “polluter pays” principle of Environmental International Law.

Keywords: climate change, international law, Global South perspective, LGBTQIAP+ community, cis-heteronormative legal morality, environmental health equity

Introduction

While climate change will affect the entire global environment, its impacts will be felt hardest by those least able to make adaptations for survival (World Economic Forum, 2023). The concept of climate justice was embedded in international legal frameworks of fairness and equity (Will & Manger-Nestler, 2021; Okereke & Coventry, 2016; Okereke, 2006). However, it fails the concerns of equity and fairness at many levels, in the international and intersectional arenas. The voiced concerns of the Global South and the unvoiced concerns of the LGBTIAP+ community have both received little to least justice under the changing climatic terrains but static international and (neo)colonial world order.

Despite advancing treaties and agreements, there is a static poly-crisis of climate justice, owing to the non-binding and lack of accountability, which fails the concerns of the Global South, while the queer community, one of the largest stakeholders of climate injustice in the sense they face disproportionate impacts, does not have representation of their concerns in legal and policy formulations. While the climate crisis is worsening each year, there is no substantial change in the dynamics of accountability and vulnerability, despite the developments in environmental jurisprudence (Gathara, 2022; World Economic Forum, 2019; MacNeil, 2025).

The LGBTQIAP+ community is discriminated against in cisgender-heteronormative State policies with respect to education (OHCHR, 2019), employment (Maji et al., 2024), housing (Muruganandhan et al., 2025), and healthcare (UNEP et al., 2020; Medina-Martínez, et al., 2021). The community is already marginalized in many social and development indices. The adversity caused by climate change not only adds to these but is aggravated due to these persisting and existing disparities.

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY AND APPROACH

This study employs a rigorous methodological framework to analyze the complex interplay between climate change, international law, and the experiences of vulnerable LGBTQIAP+ communities, particularly in the Global South. The scholarly approach taken in this paper is outlined below.

CLIMATE JUSTICE AND THE BRUNT OF CLIMATE CHANGE

Climate justice is based on principles of fair treatment and freedom from discrimination, addressing the disproportionate impact of climate change (Okereke, 2007). It recognizes that climate change disproportionately affects low-income communities, people of color, vulnerable communities, and minorities (including gender minorities) globally, and much more severely impacts the developing countries of the Global South—the places least responsible for the problem (World Bank, 2023).

The year 2024 saw the first year-long breach of the 1.5° target of the Paris Agreement 2015 (Poynting, 2024). That year was marked by recurring floods, droughts, and extreme climate conditions. Ideally, the brunt of these impacts would be proportional to those liable for the crisis, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Illustration depicting disproportionate climate impacts on the Global South

Reports from the Asian Development Bank show that India, Bangladesh, Vietnam and the Philippines have lost more than 20 billion US$ due to natural hazards linked with climate change over the last 40 years. It is estimated that these countries may lose as much as 6.7% of their GDP growth by 2100 (World Bank, 2023).

The World Bank estimates that even moderate increases in temperature could reduce crop yields by 10–20 percent by 2050 in regions such as Africa, heightening the risks of food insecurity and undernutrition, particularly among vulnerable populations (World Bank, 2015)

THE INDUSTRIALIZED VS. DEVELOPING NATIONS DEBATE

The crux of the debate is that while the USA and other Western countries push that liability for pollution and environmental degeneration should be accounted for according to the current status, the implications are that these industrialized nations have advanced at the expense of the global environment. Putting liabilities on developing countries now acts as a deterrent to their growth and advancement (Okereke, 2010).

Legal jurisprudence has evolved with economic growth. Industrialized nations are obligated by the principle of ‘absolute liability’ to abide by the conception of ‘polluter pays’. These obligations need to be legally recognized and reiterated, not left to moral-ethical rhetoric.

The Emissions Disparity

The theory of ‘common but differentiated responsibility’ in the United Nations Framework on Climate Change and the Kyoto Protocol instills the principles of fairness and equity, addressing the unequal distribution of resources and responsibility.

USA

Annual per capita CO2 emissions (metric tonnes)

China

Annual per capita CO2 emissions (metric tonnes)

49 LDCs

Annual per capita CO2 emissions (metric tonnes)

USA Emissions

Accounts for 25% of global emissions with only 4% of the population.

Source: World Bank (2012, 2023)

THE POLLUTER PAYS PRINCIPLE AND GLOBAL ACCOUNTABILITY

The concept of the “polluter pays principle” is a cornerstone of international environmental law, aiming to hold those responsible for environmental damage accountable for the costs of preventing, controlling, and remedying pollution (Adshead, 2018). However, its application in the context of global climate change presents significant challenges, particularly regarding historical emissions and the disproportionate impact on developing nations.

Legal Foundation and Avoidance of Accountability

The theory of ‘common but differentiated responsibility’ in the United Nations Framework on Climate Change and the Kyoto Protocol instills the principles of fairness and equity, addressing the unequal distribution of resources and responsibility. Despite this, “the polluters who caused climate change, the developed countries of the West do not agree to share the burdens and uphold the principle of “polluter pays” (Paterson, 1996).” This avoidance of responsibility by industrialized nations, which have historically contributed the most to greenhouse gas emissions, leaves a significant accountability gap.

Historical Emissions

Industrialized nations have advanced at the expense of the global environment. While the USA and other Western countries push that liability for pollution and environmental degeneration should be accounted for according to the current status, this neglects their historical contributions to the climate crisis.

Legal Obligations

Legal jurisprudence has evolved with economic growth. Industrialized nations are obligated by the principle of ‘absolute liability’ to abide by the conception of ‘polluter pays’. These obligations need to be legally recognized and reiterated, not left to moral-ethical rhetoric.

Economic Burden on Developing Countries

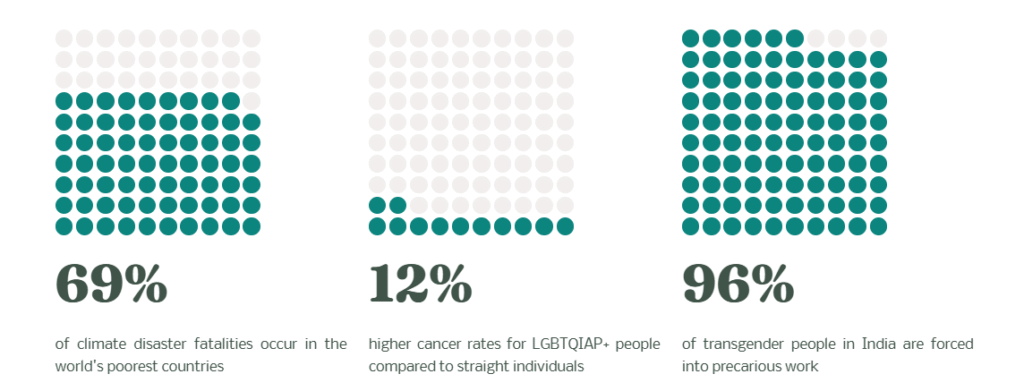

The failure to enforce the polluter pays principle places a severe economic burden on developing countries, particularly those in the Global South. “There is maldistribution of the burden of climate change upon the Global South, which feels its impacts more strongly as it is not well equipped and developed to adapt to the climatic conditions. (UNFCCC, 2023; IPCC AR6, 2022). Sixty-nine percent of worldwide deaths caused by climate-related disasters occurred in LDCs (UNCTAD, 2022).”

Financial Losses

Reports from the Asian Development Bank show that India, Bangladesh, Vietnam and the Philippines have lost more than 20 billion US$ due to natural hazards linked with climate change over the last 40 years. It is estimated that these countries may lose as much as 6.7% of their GDP growth by 2100.

Food Security Impact

The World Bank estimates that even with a temperature rise of less than 2°C, by 2050, crop yields will decrease by 10% to 20%. This increases the risk of food insecurity and malnutrition in children, which can go up to as much as 25-90%.

Challenges in Application

Despite advancements in environmental jurisprudence, “there is a static poly-crisis of climate justice, owing to the non-binding and lack of accountability, which fails the concerns of the Global South”. This lack of binding enforcement mechanisms and a concrete framework for accountability remains a major challenge in applying the polluter pays principle effectively to climate change, hindering successful implementation and leaving vulnerable nations to bear the costs.

ENVIRONMENTAL SEXISM AND INTERSECTIONALITY

The impact of global warming is most severe in Global South countries. Within these nations, vulnerable communities are most impacted due to the intersectionality of class, gender, sexual identities, caste, religion, race, disability, and age. Environmental sexism is prima facie structural violence within cisgender heteronormative (cishet) policy frameworks.

Numerous studies indicate a consistent correlation between environmental crises and existing gendered and intersectional inequalities (OECD, 2023; Djoudi et al., 2016).

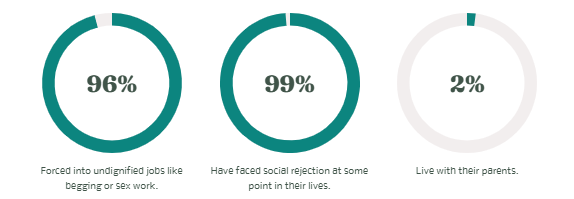

CASE STUDY: TRANSGENDERS OF INDIA

The transgender community in India (Hijras, Kinnars, etc.), as shown in Figure 2, is often forced into begging and sex work, living in marginalized, congested areas with little access to mainstream livelihoods. These “red-light areas” are often unsafe and lack climate mitigation or adaptation resources.

Figure 2: Map of India

Source: NHRC study by Kerala Development Society (Chauhan, 2018)

“With the upcoming monsoons, there will be heavy rains in Chennai and my house will also be flooded… It’s very difficult for a transgender person to get a house in the city, to make the house-owners understand.”

– A transwoman from Chennai, India (Behal, 2021) as depicted in the broader context of Figure 2’s geographical area.

Housing discrimination pushes queer individuals into segregated, dilapidated areas with severe climate hazard risks in regions like those highlighted in Figure 2. This, combined with discrimination and lack of access to resources, leads to deteriorating mental health and exacerbates climate-related disparities.

INTERNATIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL LAW: A FLAWED FRAMEWORK

Traditional approaches to international environmental law often reject distributive justice, favoring self-interest and formalistic relations. However, constructivist scholars argue that legal norms can guide international law independently of power politics.

The evolution of key international environmental agreements is illustrated in Figure 3 below.

1972 Stockholm Declaration

Linked environmental degradation to man-made activities and their harmful effects on human health.

1987 Montreal Protocol

Focused on precautionary measures for ozone depletion, emphasizing the needs of developing countries.

1989 Basel Convention

Regulated toxic waste trade, based on prior informed consent and environmentally sound disposal.

1992 Rio Declaration

Officially recognized the principle of differential treatment for developing countries in climate negotiations.

1992 UNFCCC

Outlined principles for combating climate change, including “common but differential responsibilities,” but lacked specific targets or penalties.

1997 Kyoto Protocol

Operationalized the UNFCCC with legally binding emission reduction targets for industrialized nations.

Figure 3: Evolution of International Environmental Law Framework (1972-1997)

THE TWAIL APPROACH: A CRITIQUE OF INTERNATIONAL LAW

The Third World Approach to International Law (TWAIL) argues that international law is inherently Eurocentric and perpetuates the subordination of non-European states (Anghie, 2023). It emphasizes the neo-imperialist world order and the threat of recolonization through geo-economic-political means.

Core Tenets of TWAIL

- Understands how systemic biases in International Law perpetuate the subordination of the Global South.

- Aims to eradicate the underdevelopment of the “third world” through scholarship and policy.

- Critiques the arbitrary and selective application of humanitarian intervention in favor of the West.

TWAIL on Environmental Law

- Highlights the failure of frameworks like the UNFCCC to define “loss and damage” or provide clear financial support mechanisms.

- Views the Global South’s demand for loss and damage compensation as a call for historical accountability from the Global North.

- Argues that the omission of liability and compensation in agreements like the Paris Agreement reveals Eurocentric biases.

Decolonizing Knowledge for Climate Justice

TWAIL scholars emphasize that unless there is a decolonial approach to knowledge production and inclusivity of perspectives, the ends of climate justice are far. Knowledge production itself is a site of contention. A “queer-of-color critique” challenges Eurocentric academic work that erases the lived experiences at the intersections of race and sexuality. Tackling the climate crisis requires structural reforms that address who holds negotiation power and how decision-making is organized, from grassroots to global levels. Decoloniality of discourse is decoloniality of power.

LEGAL FRAMEWORKS AND HUMAN RIGHTS OBLIGATIONS

The intersection of international human rights law and environmental protection creates a crucial framework for addressing the disproportionate impact of climate change on vulnerable populations, including LGBTQIAP+ individuals. States have clear obligations under international law to protect these communities.

International Human Rights Law

International human rights law, encompassing treaties like the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), guarantees rights such as the right to life, health, adequate housing, and non-discrimination. These rights are fundamental and extend to all individuals, irrespective of sexual orientation, gender identity, or gender expression, and must be protected in the context of climate change impacts.

State Obligations to Protect

Under international law, states have an obligation to respect, protect, and fulfill human rights. This includes taking affirmative measures to mitigate climate change and adapt to its impacts, ensuring that such actions do not discriminate against or disproportionately harm vulnerable groups. States must identify and address the specific vulnerabilities of LGBTQIAP+ communities to climate-related disasters and displacement.

The Yogyakarta Principles

The Yogyakarta Principles on the Application of International Human Rights Law in relation to Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity (2007), and their update (Yogyakarta Principles +10, 2017), explicitly affirm states’ obligations to protect LGBTQIAP+ individuals from discrimination and violence, including in humanitarian situations. Principle 16 (The Right to Social Security and to Protection) and Principle 17 (The Right to Adequate Housing) are particularly relevant, asserting protection from displacement due to natural disasters and ensuring equitable access to safe housing, regardless of sexual orientation or gender identity.

Regional Human Rights Mechanisms

Regional human rights bodies, such as the Inter-American Court of Human Rights and the European Court of Human Rights, have increasingly recognized the link between human rights and environmental protection. While direct case law explicitly linking LGBTQIAP+ rights to climate change is emerging, these mechanisms establish precedents for the protection of marginalized groups from state neglect or harmful actions, providing avenues for future advocacy and litigation concerning climate justice.

Legal Precedents and Case Law

While specific case law directly addressing the rights of LGBTQIAP+ individuals in relation to climate is still developing, general principles derived from human rights litigation are highly relevant. Cases affirming the right to non-discrimination, protection against arbitrary displacement, and the right to a healthy environment can be leveraged. For instance, decisions emphasizing the extraterritorial obligations of states regarding human rights and environmental harm set important precedents for holding powerful nations accountable for their climate impact on vulnerable communities globally.

THE QUEER CONCERNS: AN INVISIBLE CRISIS

Climate change impacts queer people more significantly than the general population. This is exacerbated by discriminatory laws and policies that create a cycle of vulnerability.

Policy and Legal Frameworks Adding to Vulnerability

State policies often ignore the need for affirmative action for the queer community in employment, housing, and healthcare. The lack of legal recognition for same-sex marriage, for example, denies couples access to housing rights, insurance, and other benefits available to heterosexual couples. This societal and legal exclusion leads to:

Climate Change and Queerphobia

Queerphobic narratives often link natural disasters to divine punishment for homosexuality, as seen after Hurricane Katrina when religious leaders blamed LGBTQ+ communities for the disaster (Repent America, 2005). This structural violence is evident globally:

- 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami: The Aravani (transgender) community in Tamil Nadu was excluded from relief aid and official death counts because they lacked ration cards.

- 2011 Japan Tsunami: Relief shelters had binary bathing and washroom facilities, excluding third-gender individuals.

Climate justice must address the intersection of climate change and social inequalities experienced as structural violence. This requires decolonizing knowledge, sensitizing policies to gender and sexuality, and enabling the stories of impacted communities to be heard.

HEALTH DISPARITIES AND ENVIRONMENTAL EXPOSURE

The intersection of systemic discrimination and environmental injustice creates profound health disparities for LGBTQIAP+ communities. (Goldsmith & Bell, 2022) These communities often face compounded vulnerabilities, leading to a range of adverse health outcomes, particularly in the face of climate change.

Higher Rates of Respiratory Diseases

Housing discrimination pushes queer individuals into segregated, dilapidated areas with higher concentrations of air pollutants and greater health risks. This leads to significantly higher rates of respiratory diseases among LGBTQIAP+ communities.

Limited Healthcare Access in Emergencies

During climate emergencies, LGBTQIAP+ individuals often face limited access to adequate healthcare services due to discrimination, lack of affirming spaces, and pre-existing societal exclusion, exacerbating their health vulnerabilities.

Compounded Mental Health Impacts

The mental health impacts of climate anxiety are significantly compounded by social discrimination, homophobia, and lack of tolerance. This contributes to deteriorating mental health and behavioral exclusion within queer communities.

Increased Health Risks During Extreme Weather

Specific health vulnerabilities during extreme weather events are heightened for LGBTQIAP+ individuals, who may lack access to safe shelters, essential resources, or supportive networks. Studies show the cancer risk in the LGBTQIAP+ community is 12.3% higher than that of heterosexual partners (Collins, 2017a; Collins, 2017b), highlighting pre-existing health disparities.

These disproportionate climate-related health outcomes demonstrate the urgent need to address the systemic inequalities that place queer communities at increased risk, advocating for inclusive policies and equitable access to resources.

THE ECO-HOMONORMATIVE JURISPRUDENCE

The concept of climate justice is based on ensuring fair treatment and non-discrimination. To test the principle of Common but Differential Responsibilities (CBDR) as a legal obligation, its standing must be traced through the sources of international law. However, analysis shows that the principle lacks binding legal force.

The failure of the CBDR principle to ensure climate justice highlights the need for negotiations with inclusive representation of all stakeholders, including the LGBTQIAP+ community, to break the structural anarchy of the international order.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR INCLUSIVE CLIMATE POLICY

Addressing climate change’s disproportionate impact on LGBTQIAP+ communities requires integrating their voices, experiences, and data into policy-making and implementation. These recommendations outline key steps for inclusive climate justice.

Integrating LGBTQIAP+ Voices in Climate Negotiations

Ensure Representation in Delegations

Advocate for LGBTQIAP+ individuals and organization representatives in national and international climate negotiation delegations.

Capacity Building for Advocacy

Provide funding and training for LGBTQIAP+ organizations to enhance their capacity in climate policy discussions and articulate specific needs.

Develop Inclusive Policy Language

Promote gender-inclusive language, explicitly referencing sexual orientation and gender identity in climate policies, action plans, and disaster response.

Establish Safe Consultation Mechanisms

Create secure platforms for LGBTQIAP+ communities to provide input on climate policies without fear of discrimination.

Suggestions for Data Collection and Research Methodologies

Accurate, inclusive data is crucial for understanding vulnerabilities and designing effective interventions. Methodologies must capture the unique experiences of diverse LGBTQIAP+ populations.

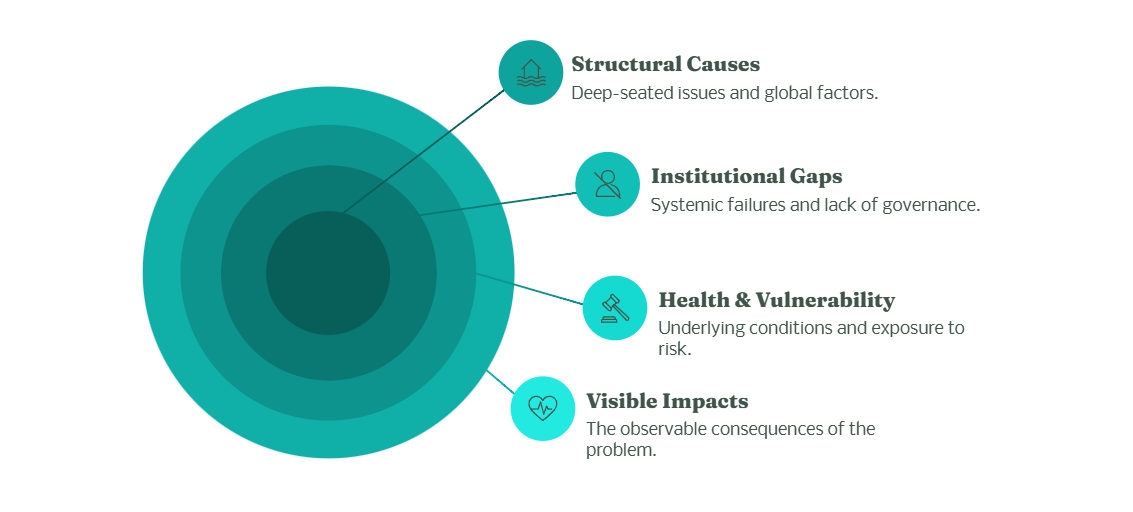

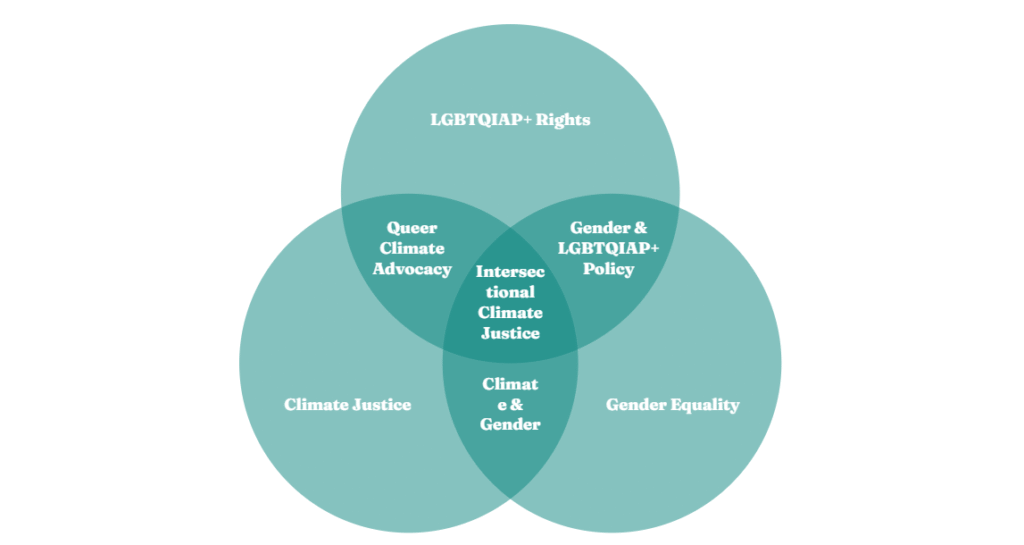

Framework for Intersectional Climate Justice Approaches

An intersectional approach acknowledges that vulnerabilities are shaped by multiple, overlapping identities and power dynamics. As illustrated in Figure 4, this framework highlights the critical intersections of Climate Justice, Gender Equality, and LGBTQIAP+ Rights.

Figure 4: A three-circle Venn diagram showing the overlapping areas of Climate Justice, Gender Equality, and LGBTQIAP+ Rights, with Intersectional Climate Justice at the center.

- Recognize Intersecting Vulnerabilities: Acknowledge how sexual orientation, gender identity, race, class, disability, and other factors create unique climate risks. This recognition is fundamental to the concept of Intersectional Climate Justice depicted in Figure 4.

- Adopt a Rights-Based Approach: Frame climate action within a human rights framework, upholding the rights of all, including LGBTQIAP+ persons, to a safe, healthy environment.

- Promote Decolonial Knowledge: Integrate indigenous and traditional knowledge systems that embody holistic and sustainable environmental relationships, challenging colonial narratives.

Role of Civil Society and Advocacy Organizations

Civil society organizations are critical actors in bridging the gap between policy and practice, advocating for marginalized communities, and providing essential services.

Implementation Strategies for Inclusive Climate Adaptation

Effective climate adaptation plans must be designed with the diverse needs of all communities in mind to ensure equitable outcomes.

Safe and Affirming Shelters

Establish disaster shelters that are safe and welcoming for all gender identities and sexual orientations, with non-binary facilities and trained staff.

Economic Empowerment

Support economic resilience programs for LGBTQIAP+ individuals, especially those in climate-vulnerable sectors, to mitigate livelihood disruptions.

Inclusive Early Warning Systems

Ensure climate early warning systems and communication are accessible and culturally sensitive to LGBTQIAP+ communities, including diverse language and communication methods.

Healthcare Accessibility

Integrate LGBTQIAP+ health considerations into disaster preparedness and response, ensuring access to affirming medical care and mental health support.

ANALYSIS AND THE BLISS OF IGNORANCENALYSIS AND THE BLISS OF IGNORANCE

Climate justice requires sustainable legal solutions addressing injustices caused and aggravated by climate change. However, there is a significant lack of research, data, and healthcare surveys focused on disproportionately affected communities, making their inclusion in decision-making crucial.

The Six Pillars of Climate Justice

As enumerated by the Center for Climate Justice, University of California (Berkeley Climate Equity Research Collective, 2023)

These six pillars, as illustrated in Figure 5 below, provide a comprehensive framework for understanding climate justice.

Figure 5: The Six Pillars of Climate Justice Framework

Climate narratives that exclude the LGBTQIAP+ perspective are based on a masculinist ideology, which ecofeminist Greta Gaard argues is the root cause of climate change. Intersectionality is not just about intersecting identities but about the intersecting nature of oppression. The plight of the LGBTQIAP+ community in the Global South is an analysis of developmental economy failures, ecological crises, and the misery of those whose human rights violations never make it into official records.

CONCLUSION

The multipolar international order often sees the interests of dominant players crush the voices of weaker nations, a reality highlighted by TWAIL. Climate injustice is a pressing issue, but it is not being approached inclusively. The framework fails to cater to the special needs of the Global South or the LGBTQIAP+ community, which often lacks a voice even in municipal law.

It is the need of the hour for more inclusive dialogue, decision-making, research, and educational engagement that prioritizes community-based and community-led solutions, giving due consideration to indigenous approaches. The intersection of LGBTQIAP+ identities with Indigenous knowledge systems offers a versatile gateway to decolonization, as many pre-colonial cultures recognized gender diversity without stigma. This collaborative vision is exemplified in Figure 6.

The specific circumstances of the LGBTQIAP+ community, especially in the Global South, make it significant to voice their concerns in international climate negotiations. They are a third world within the third world, and their inclusion is paramount for achieving true climate justice (as depicted in Figure 6).

Figure 6: Diverse group (LGBTQ+ individuals and Global South representatives) collaborating for a healing planet.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The author(s) gratefully acknowledge the support of the 2024 Humboldt Residency Programme, Alexander von Humboldt Foundation, in making this special issue Bridging power and knowledge: Addressing global imbalances in knowledge systems for sustainable futures possible.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author declares no conflict of interest.

FUNDING

This project received funding from the 2024 Humboldt Residency Programme of the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation.

REFERENCES

Adshead, J. (2018). The application and development of the polluter-pays principle across international, European Union and domestic English law. Journal of Environmental Law, 30(2), 259–284.

Anghie, A. (2023). Rethinking international law: A TWAIL retrospective. European Journal of International Law, 34(1), 7–35.

Behal, A. (2021, August 15). How climate change is affecting the LGBTQIA+ community. Down To Earth. https://www.downtoearth.org.in/blog/climate-change/how-climate-change-is-affecting-the-lgbtqia-community-78456

Center for Climate Justice, University of California, Berkeley. (2023). Six Pillars of Climate Justice. https://centerclimatejustice.universityofcalifornia.edu/what-is-climate-justice/

Chauhan, N. (2018, August 13). Left alone: Just 2% of trans people stay with parents. The Times of India. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/left-alone-just-2-of-trans-people-stay-with-parents/articleshow/65380226.cms

Collins, T. W., Grineski, S. E., & Morales, D. X. (2017a). Environmental injustice and sexual minority health disparities: A national study of inequitable health risks from air pollution among same-sex partners. Social Science & Medicine, 191, 38–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.08.040

Collins, T. W., Grineski, S. E., & Morales, D. X. (2017b). Sexual orientation, gender, and environmental injustice: Unequal carcinogenic air pollution risks in Greater Houston. Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 107(1), 72–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2016.1218270

Djoudi, H., Locatelli, B., Vaast, C., Asher, K., Brockhaus, M., & Sijapati, B. B. (2016). Beyond dichotomies: Gender and intersecting inequalities in climate change studies. Ambio, 45(3), 248–262. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-016-0825-2

Dominey-Howes, D., Gorman-Murray, A., & McKinnon, S. (2014). Queering disasters: On the need to account for LGBTI experiences in natural disaster contexts. Gender, Place & Culture, 21(7), 905–918.

Gaillard, J. C., Sanz, K., Balgos, B. C., Dalisay, S. N. M., Gorman-Murray, A., Smith, F., & Toelupe, V. (2017). Beyond men and women: A critical perspective on gender and disaster. Disasters, 41(3), 429–447.

Gathara, P. (2022, November 19). The West will not act on climate change until it feels its pain. Al Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2022/11/19/global-south-pleas-wont-get-the-west-to-act-on-climate-change

Goldsmith L., & Bell, M. L. (2022). Queering environmental justice: Unequal environmental health burden on the LGBTQ+ community. American Journal of Public Health, 112(1), 79–87. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2021.306406

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. (2022). Climate change 2022: Impacts, adaptation and vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press.

MacNeil, R. (2025). The case for a permanent US withdrawal from the Paris Accord. Australian Journal of International Affairs, XX(YY), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/10357718.2025.2482701

Maji, S., Yadav, N., & Gupta, P. (2024). LGBTQ+ in workplace: A systematic review and reconsideration. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion, 43(2), 313–360. https://doi.org/10.1108/EDI-02-2022-0049

Medina-Martínez, J., Saus-Ortega, C., Sánchez-Lorente, M. M., Sosa-Palanca, E. M., García-Martínez, P., & Mármol-López, M. I. (2021). Health inequities in LGBT people and nursing interventions to reduce them: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(22), 11801. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182211801

Muruganandhan, S., Kumar, A. R., Saiesakkisakthivel, R., Abishek, M., Sivasubramanian, K., & Muinao, M. (2025). Gender discrimination and empowerment of LGBT community in India: A systematic review. In M. Al Mubarak (Ed.), Sustainable digital technology and ethics in an ever-changing environment (Vol. 237, pp. 36). Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-86708-8_36

Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. (2019). Educational rights and sexual orientation. United Nations.

Okereke, C. (2006). Global environmental sustainability: Intragenerational equity and conceptions of justice in multilateral environmental regimes. Geoforum, 37(5), 725–738. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-7185(06)00006-6

Okereke, C. (2007). Global justice and neoliberal environmental governance: Ethics, sustainable development and international co-operation. Routledge.

Okereke, C. (2010). Climate justice and the international regime: Before, during and after Copenhagen. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 1(5), 645–654.

Okereke, C., & Coventry, P. (2016). Climate justice and the international regime: Before, during, and after Paris. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 7(6), 834–851.

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2023). Gender and climate change: Policy responses. OECD Publishing.

Paterson, M. (1996). Global warming and global politics. Routledge.

Pincha, C. (2008). Gender sensitive disaster management: A toolkit for practitioners. Earthworm Books.

Poynting, M. (2024, February 8). World’s first year-long breach of key 1.5C warming limit. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-68110310

Repent America. (2005, August 31). Religious leader blames hurricane on gays. OutTraveler/Advocate. https://www.advocate.com/news/2005/09/01/religious-leader-blames-hurricane-gays

UNCTAD. (2022). The least developed countries report 2022. https://unctad.org/publication/least-developed-countries-report-2022

UNEP, UN Women, UNDP, & UNDPPA. (2020). Gender, climate and security: Sustaining inclusive peace on the frontlines of climate change. https://www.unwomen.org/sites/default/files/Headquarters/Attachments/Sections/Library/Publications/2020/Gender-climate-and-security-en.pdf

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. (2023). Climate change and vulnerable populations: Assessment report. United Nations.

Will, U., & Manger-Nestler, C. (2021). Fairness, equity, and justice in the Paris Agreement: Terms and operationalization of differentiation. Leiden Journal of International Law, 34(2), 397–420. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0922156521000078

World Bank. (2015). Climate-smart agriculture: A call to action. World Bank. https://www.worldbank.org/content/dam/Worldbank/document/CSA_Brochure_web_WB.pd

World Bank. (2023). Social dimensions of climate change. https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/social-dimensions-of-climate-change

World Economic Forum. (2019). The global risks report 2019. World Economic Forum.

World Economic Forum. (2023). The global risks report 2023. World Economic Forum.

Yogyakarta Principles. (2007). The Yogyakarta Principles on the Application of International Human Rights Law in relation to Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity. http://www.yogyakartaprinciples.org/

Yogyakarta Principles Plus 10. (2017). Additional principles and state obligations on the application of international human rights law in relation to sexual orientation, gender identity, gender expression and sex characteristics. http://yogyakartaprinciples.org/principles-en/yp10/

ABOUT THE AUTHOR(S)

Surabhi is a Master’s student at National Law University, Jodhpur (2025–26), and serves as State Vice President at the Women’s Indian Chamber of Commerce and Industry (WICCI). She founded Project WIND, focusing on pro-bono environmental litigation and climate justice. As a Climate READY fellow (2024–25), she has contributed to climate pedagogy reforms. Recognized as a top 5 Global Ambassador at the 2022 GPS EmpoWomen Summit by the US Embassy, Surabhi’s work spans gender, sexuality, marginalized rights, and social justice. She is also an artist, advocate, and activist.

Received: January 23, 2025

Accepted: July 15, 2025

Published: October 31, 2025

Citation: Srivastava, S. (2025). Climate change and the Global South: An intersectional study of the impact of climate change on LGBTQIAP+. SustainE, 3(1), 114–139. In A. Akinsemolu, A. Eimer, & S. Iqbal (Eds.), Bridging power and knowledge: Addressing global imbalances in knowledge systems for sustainable futures [Special issue]. https://doi.org/10.55366/suse.v3i1.6

Disclaimer: The opinions and statements expressed in this article are the author(s) sole responsibility and do not necessarily reflect the viewpoints of their affiliated organizations, the publisher, the hosted journal, the editors, or the reviewers. Furthermore, any product evaluated in this article or claims made by its manufacturer are not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Distributed under Creative Commons CC-BY 4.0