AUDIO-VISUAL COMMENTARY

YIAVHA

Youth Initiative Against Violence and Human Rights Abuse, Nigeria

This article is part of a special issue titled Bridging Power and Knowledge: Addressing Global Imbalances in Knowledge Systems for Sustainable Futures.

PLAIN-LANGUAGE SUMMARY

WATCH A SUMMARY OF THE ARTICLE

LISTEN TO THE PODCAST

Abstract

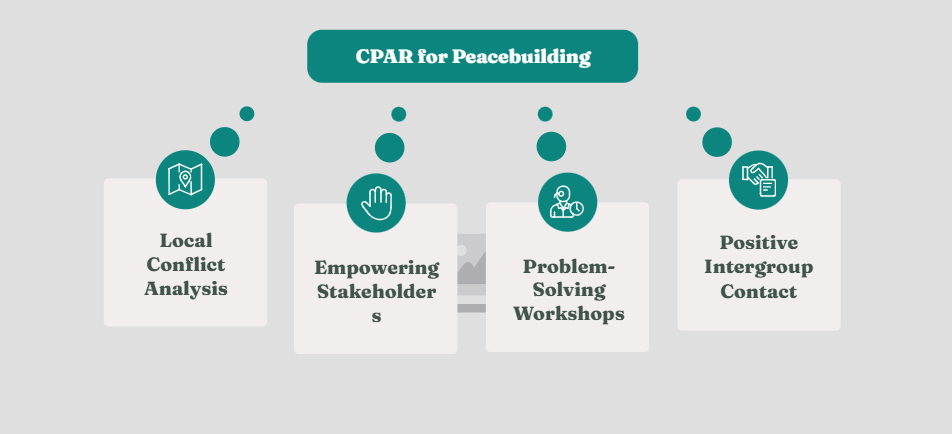

Community Participatory Action Research (CPAR) in peacebuilding is often framed as an approach to ensure that conflict analyses are locally-informed and as means to empower local stakeholders. However, CPAR can also in itself be an approach to building peace. This documentary shows how the Youth Initiative Against Violence and Human Rights Abuse (YIAVHA) used CPAR to analyze conflict dynamics in Riyom, Plateau State, Nigeria, and in the process, lessened the outbreaks of violence between farmers and herders and promoted continued cooperation between groups. This provides further evidence that CPAR itself can act as a form of problem-solving workshop that promotes positive intergroup contact—a finding that has significant implications for peacebuilding efforts around the world.

Keywords: community participatory action research, peacebuilding, farmer-herder conflict, Nigeria, intergroup contact theory, problem-solving workshops

Introduction

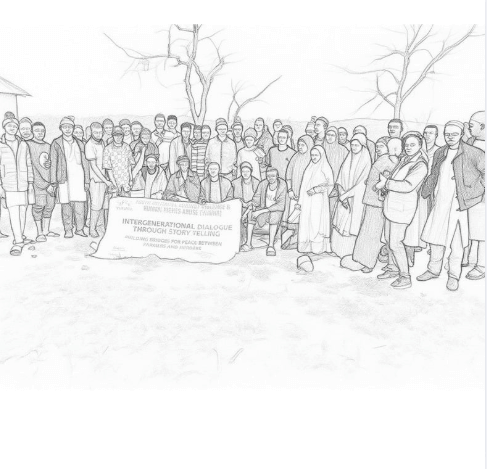

Two of the fundamental principles of peacebuilding are that programs need to be contextually-relevant and designed with input from the stakeholders involved (Lederach 1997; Schirch 2013). This has spurred a host of participatory analysis and design processes ranging from collaborative analysis and community consultations to co-designing peacebuilding interventions with community members (Renoir et al. 2024; Michael et al. 2024; Hill et al. 2024). In many of these, however, the non-governmental organization or donor remains the primary decision-maker. In contrast, community participatory action research (CPAR) embraces community members as co-creators of knowledge (Michael et al. 2024; Renoir et al. 2024). As Hill et al. argue, “only by asking—and actually listening to—members of particular communities can we hope to learn what types of interventions actually change people’s lived experiences for the better on a day-to-day basis” (2024, 211). CPAR encourages local knowledge, provides an opportunity for mutual discovery, amplifies voices often sidelined or silenced altogether, and “provides a platform for local actors to participate in real processes of conflict transformation” (Hill et al. 2024, 213). The Youth Initiative Against Violence and Human Rights Abuse’s (YIAVHA) Building Bridges for Peace project provides a model of not only how to do so, but also how this can be done in a way to also foster relationship-building and promote locally-driven problem-solving workshops in violence-affected contexts (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Community dialogue sessions bringing together farmers and herders through YIAVHA’s participatory research approach

THE HISTORICAL AND SOCIO-POLITICAL BACKGROUND OF VIOLENCE BETWEEN FARMERS AND HERDERS IN NIGERIA

Violent conflicts permeate Nigeria, yet farmer-herder clashes receive insufficient research or state attention. This neglect is especially evident in Riyom LGA, Plateau State, where cyclical violence is exacerbated by state inaction and other conflict issues. This section explains the historical and socio-political roots of this violence in Riyom LGA, placing it within the broader Nigerian context.

Since Nigeria’s return to democratic governance in 1999, the country has experienced decades of violence from extremist groups, separatist movements, criminal networks, and ethnoreligious clashes. These conflicts have disrupted livelihoods, displaced hundreds of thousands, reversed economic gains, and inflamed ethnoreligious divisions (Njokwu & Obiukwu, 2025; Ojo, Oyewole & Aina, 2023). While attention often focuses on Boko Haram and other extremist groups (Abdulahi & Mukhtar, 2022; Abdullah, 2019), farmer-herder clashes are among the most destructive, leading to significant displacement, casualties, and livelihood disruption for tens of thousands (Adesola & Akerele, 2025).

Root Causes of Farmer-Herder Conflict

Despite the rising significance of farmer-herder violence over the last decade, the state’s response remains largely ad-hoc and, in some areas, nonexistent. This is because the state treats the clashes as mere occupational struggles and communal disturbances that do not threaten Nigeria’s territorial integrity or sovereignty (Oginni, 2024; Osasona, 2023). However, farmer-herder violence has claimed as many lives as banditry and insurgency, disrupting rural livelihoods, inducing mass displacement, severing the social fabric (Brottem, 2021), and reconfiguring the demographic landscape of affected communities. Furthermore, this violence and resulting livelihood loss drives victims to turn to banditry for survival (Oginni, 2024).

Although often framed ethnoreligiously or as a struggle for resources, farmer-herder violence is driven by a multitude of factors, including common regional patterns (e.g., climate change and discriminatory land policies) and community-specific issues (Chukwuma, 2020). Recently, the intertwined nature of political, economic, and social factors has become clearer, reinforcing and deepening the clashes. Babatunde and Ibnouf (2024) contend conflicts arise when social relations mobilize to determine resource access, or when rural development initiatives almost exclusively benefit one group. This usually leads to dissatisfaction toward the state and the favored group, serving as an impetus for violent resistance against perceived annihilation and state neglect of their common stake (Egwu, 2016). This situation is particularly dangerous in polarized communities where the actions of municipal actors (state officials, security agencies, traditional rulers, and others) are perceived, rightly or wrongly, to contribute to the unequal distribution of essential resources.

Plateau State Context

In Plateau State, farmer-herder clashes have become endemic over the last two decades. Beyond the general factors, conflicts here are also driven by resource management politics and municipal leaders’ decisions that trigger backlashes from specific groups. Clashes are closely associated with decades of indigene-settler divides (Egwu, 2011), which have balkanised communities into separate enclaves where people prefer to reside with those of the same ethnicity and religion. This is exacerbated by categorising farmers as indigenous and herders as settlers, making reconciliation almost impossible and leading to widespread entrenched profiling—one group as complicit and the other as victims—in every attack on the Plateau (Ibrahim & Dabugat, 2016; Sha, 2005). Farmers, often Christian ethnic groups (e.g. Berom, Afizere, Anaguta), claim indigene status, while herders, often Hausa or Fulani, are viewed by many communities and state leaders as settlers. The stalemate in conflict transformation and lack of state security have fueled rising mutual suspicions, disdain, and the proliferation of ethnic militias, neighbourhood watch groups, and vigilantes. The existence of these informal security outfits underscores the Nigerian State’s low capacity to exclusively organize violence to safeguard civilians (Tapscott, 2021).

Riyom local government has witnessed unprecedented killings and displacement. These areas have been described as places where violence and property destruction defy peace dialogues, cautions of religious and traditional leaders, and military dexterity (Babatunde & Ibnouf, 2024).

Historical Symbiotic Relationships

Violence between farmers and herders in Riyom LGA is dynamic, featuring periods of violent clashes alternating with tepid peace where underlying conflict factors remain unresolved. In 2024, some communities reported a cessation of open violent clashes, though tensions remained high and violence could return. Lands remain inaccessible to both groups for safe farming, grazing, and living. Furthermore, the lack of a known, deliberate structure for consistent psychosocial support to victims, especially children, poses a potential risk for future insecurity as intolerance may prevail in adulthood. This suggests pessimism overshadows the potential for peaceful coexistence and fair resource access for diverse occupational groups.

While farmer-herder violence has become increasingly commonplace over the last decade, historically, peaceful coexistence was the norm (Higazi 2018). Previously, they had a symbiotic relationship, trading food for natural fertilizer (e.g., cow dung) and relying on traditional mechanisms to resolve conflicts (Bagu and Smith 2017). The introduction of commercial fertilizer and the abandonment of the Cattle Tax in 1980 (which contributed to community development) broke down the social contract and traditional conflict resolution mechanisms between farmers and herders (Bagu and Smith 2017). These changes occurred amidst increasing politicisation of ethnicity, climate change, poor governance, and zero-sum politics post-1999, further eroding and fracturing these relationships.

BUILDING PEACE THROUGH COMMUNITY PARTICIPATORY ACTION RESEARCH

In 2023, YIAVHA launched a peacebuilding program, Building Bridges for Peace, in Riyom Local Government Area, a rural area of Plateau State, Nigeria. Riyom LGA had experienced recurring violent conflict between farmers and herders driven by a range of root causes and exacerbating factors (YIAVHA 2024). While the violence was often depicted as between farmers and herders, it intersected and was also shaped by criminality (e.g. banditry), legacies of ethnic politicization, poor governance, weak security, proliferation of arms, and historical grievances between ethnic and religious groups (YIAVHA 2024; IPCR 2017; Mustapha et al. 2018; Higazi 2016). In addition, these conflict factors were compounded by climate change which reshaped which land was fertile and the availability of water sources (YIAVHA 2024; Bagu and Smith 2017). While community members were aware of many of these factors, there was little shared understanding of how they intersected or how different community members viewed them.

CPAR Methodology and Implementation

Youth Initiative Against Violence and Human Rights Abuse (YIAVHA)’s CPAR approach worked with community members from across Riyom LGA to conduct a systems analysis of the conflict dynamics in the LGA. Engaging community members as part of the research team, YIAVHA surveyed 330 community members, conducted 25 key informant interviews, and facilitated 19 community dialogues with a total of 1,033 participants. It is worth noting that in contrast to some peacebuilding approaches that engage key stakeholders and invite them to discussions held at hotels, these activities were primarily done within the communities themselves. This approach provided a real-time analysis of the conflict dynamics, and in the process, built a shared understanding about them and how different community members had experienced them.

Community Members Surveyed

Comprehensive data collection

Key Informant Interviews

In-depth stakeholder perspectives

Community Dialogues

Facilitated group discussions

Total Participants

Broad community engagement

The participatory nature of the research fostered a common understanding of how the violence affected groups (such as Berom farmers and Fulani herders) and organically identified areas for intervention. Through the CPAR project, influential Berom and Fulani leaders built relationships and trust, enabling them to deescalate tensions by reaching out to each other when conflicts arose, thus preventing violence.

Drawing on its past experience facilitating peacebuilding programs, YIAVHA also examined specific peacebuilding approaches to address the key conflict drivers identified in Riyom. These approaches included joint farming and intergenerational dialogue models, which brought together youth from Berom farmers and Fulani herders communities to counter stereotypes, promote a shared understanding of conflict dynamics, and build lasting relationships. The initiative also incorporated citizens’ security meetings as a dialogue mechanism for local power holders to address emerging conflicts across target communities.

IMPACT AND IMPLICATIONS FOR PEACEBUILDING THEORY

Youth Initiative Against Violence and Human Rights Abuse, YIAVHA’s Building Bridges for Peace was a CPAR initiative analyzing violent conflicts in Riyom LGA, Plateau State. It utilized a systems analysis approach exploring the key factors driving farmer-herder conflict and other violence in Riyom, Nigeria, and how interventions like intergenerational storytelling, joint farming initiatives, exchange visits, and inter-communal dialogues could foster peace and reconciliation. Although primarily research-focused, exploring only the relevance of these peacebuilding activities, the project’s participatory approach itself had a positive impact on the communities.

Documented Impacts

An impact evaluation conducted in 2024 found that the Building Bridges for Peace project led to a reduction in violent incidents and farm- and grazing-related conflicts, promoted socio-economics and livelihoods by sparking joint farming initiatives (Figure 2), improved community dialogue and community-driven accountability mechanisms, increased youth involvement in peacebuilding, facilitated greater access to land for safe farming and grazing, and contributed to communities being more open to exchanges with various ethnoreligious groups which are also captured in the documentary (YIAVHA 2024b). These impacts show evidence of how the participatory approach of CPAR initiatives acts as a combination of problem-solving workshops and facilitates relationship-building contact between groups. As d’Estreé has argued, the impact of intergroup contact is stronger when participants have something to collectively work on together – which is exactly what the CPAR offered (d’Estrée 2012). This echoes the importance of problem-solving workshops (Kelman 1972; 2008) and continued relevance of Intergroup Contact Theory (Wagner and Hewstone 2012; Grady et al. 2023) that underlies many peacebuilding approaches.

Reduced Violence

Decrease in violent incidents and farm/grazing-related conflicts

Economic Cooperation

Joint farming initiatives improving livelihoods and relationships

Enhanced Dialogue

Improved community-driven accountability mechanisms

Youth Engagement

Increased youth involvement in peacebuilding activities

Land Access

Greater access to land for safe farming and grazing

Openness

Communities more open to exchanges with different groups

Figure 2: Joint farming initiatives demonstrating cooperation between previously conflicted groups.

CONCLUSION

The CPAR approach utilized by YIAVHA was intended to create a robust and timely understanding of the conflict dynamics and potential responses in Riyom LGA, Plateau State. However, because of the participatory approach, involved community members built relationships and trust with individuals and groups they previously viewed as their enemy. This enabled communication across historic divisions, the establishment of locally-driven conflict resolution mechanisms, and promoted sustained collaborations in the form of joint farming initiatives. In doing so, the act of conducting participatory research itself had a positive impact on peace in Riyom. This study provides further evidence of how CPAR itself offers peacebuilding gains as previously argued by Hill et al. (2024). At a time when resources supporting peacebuilding are on the decline, and there is a global drive for localization, the YIAVHA CPAR model highlights the power of dialogue, community ownership, collective action, intergenerational collaboration, and non-violent coexistence strategies.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The author(s) gratefully acknowledge the support of the 2024 Humboldt Residency Programme, Alexander von Humboldt Foundation, in making this special issue Bridging power and knowledge: Addressing global imbalances in knowledge systems for sustainable futures possible.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author declares no conflict of interest

FUNDING

This project received funding from the 2024 Humboldt Residency Programme of the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation.

REFERENCES

Abdulahi, A. S., & Mukhtar, J. (2022). Armed banditry as a security challenge in Northwestern Nigeria. African Journal of Sociological and Psychological Studies, 2(1), 45–62. https://doi.org/10.31920/2752-6585/2022/v2n1a3

Abdullah, A. (2019). Rural banditry, regional security and integration in West Africa. Journal of Social and Political Sciences, 2(3), 644–654. https://doi.org/10.31014/aior.1991.02.03.107

Adesola, F., & Akerele, E. (2025). Borders and banditry in Nigeria. SN Social Sciences, 5(16). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43545-025-01050-8

Babatunde, A. B., & Ibnouf, F. O. (2024). The dynamics of herder-farmer conflicts in Plateau State, Nigeria, and Central Darfur State, Sudan. African Studies Review, 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1017/asr.2024.45

Bagu, C., & Smith, K. (2017). Past is prologue: Criminality & reprisal attacks in Nigeria’s Middle Belt. Search for Common Ground.

Brottem, L. (2021). The growing complexity of farmer-herder conflict in West and Central Africa. Africa Security Brief, 39. https://africacenter.org/publication/growing-complexity-farmer-herder-conflict-west-central-africa/

Chukwuma, K. H. (2020). Constructing the herder–farmer conflict as (in)security in Nigeria. African Security, 13(1), 54–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/19392206.2020.1732703

Egwu, S. (2011). Ethno-religious conflicts and national security in Nigeria: Illustrations from the Middle Belt. In S. Adejumobi (Ed.), State, economy, and society in post-military Nigeria (pp. 73–95). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230117594_3

Egwu, S. (2016). The political economy of rural banditry in contemporary Nigeria. In M. J. Kuna & J. Ibrahim (Eds.), Rural banditry and conflicts in Northern Nigeria (pp. 37–52). Centre for Democracy and Development.

Estrée, T. P. d’. (2012). Addressing intractable conflict through interactive problem-solving. In L. R. Tropp (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of intergroup conflict (pp. 425–441). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199747672.013.0014

Grady, C., Wolfe, R., Dawop, D., & Inks, L. (2023). How contact can promote societal change amid conflict: An intergroup contact field experiment in Nigeria. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 120(43), e2304882120. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2304882120

Higazi, A. (2016). Farmer-pastoralist conflicts on the Jos Plateau, Central Nigeria: Security responses of local vigilantes and the Nigerian state. Conflict, Security & Development, 16(4), 365–385. https://doi.org/10.1080/14678802.2016.1200314

Higazi, A. (2018). Rural insecurity on the Jos Plateau: Livelihoods, land & cattle amid religious reform & violent conflict. In A. R. Mustapha & D. Ehrhardt (Eds.), Creed and grievance: Muslim-Christian relations and conflict resolution in Northern Nigeria (pp. 115–142). Boydell & Brewer.

Hill, T., Siira, K., & Stoumen, N. (2024). Participatory action research: Mutual inquiry for effective local peacebuilding. In S. L. Connaughton & J. R. Linabary (Eds.), Are we making a difference? Global and local efforts to assess peacebuilding effectiveness (pp. 189–206). Rowman & Littlefield.

Ibrahim, J., & Dabugat, K. (2016). Rural banditry and hate speech in Northern Nigeria: Fertile ground for the construction of dangerous narratives in the media. In M. J. Kuna & J. Ibrahim (Eds.), Rural banditry and conflicts in Northern Nigeria (pp. 115–134). Centre for Democracy and Development.

Institute for Peace and Conflict Resolution (IPCR). (2017). Strategic conflict assessment of Nigeria: Consolidated and zonal reports. Federal Government of Nigeria.

Kelman, H. C. (1972). The problem-solving workshop in conflict resolution. In H. C. Kelman (Ed.), Communication in international politics (pp. 168–187). University of Illinois Press.

Kelman, H. C. (2008). Evaluating the contributions of interactive problem solving to the resolution of ethnonational conflicts. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 14(1), 29–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/10781910701839767

Lederach, J. P. (1997). Building peace: Sustainable reconciliation in divided societies. United States Institute of Peace Press.

Michael, S., Hook, K., Tadevosyan, M., & Allen, S. (2024). Locally useful evidence: Re-centering knowledge creation for local peace work. In S. L. Connaughton & J. R. Linabary (Eds.), Are we making a difference? Global and local efforts to assess peacebuilding effectiveness (pp. 207–224). Rowman & Littlefield.

Mustapha, A. R., Higazi, A., Lar, J., & Chromy, K. (2018). Jos fear & violence in Central Nigeria. In A. R. Mustapha & D. Ehrhardt (Eds.), Creed and grievance: Muslim-Christian relations and conflict resolution in Northern Nigeria (pp. 143–162). Boydell & Brewer.

Njoku, E. C., & Obiukwu, C. I. (2025). The nexus between insurgency, armed banditry, and secessionist movements: Revisiting Nigeria’s indivisibility. Journal of Security Management, Policy & Administration, 2(1). https://jsmpa.com.ng/wp-content/articles/published_paper/volume-2/issue-1/MNy6Cn5o.pdf

Oginni, O. S. (2024). How to stop “Jihadi Banditry” from becoming the new normal in the Lake Chad Basin. BICC Policy Brief. https://bicc.de/Publikationen/How%20to%20Stop%20Jihadi%20Banditry%20Becoming%20New%20Normal.pdf

Ojo, J. S., Oyewole, S., & Aina, F. (2023). Forces of terror: Armed banditry and insecurity in North-West Nigeria. Democracy and Security, 19(4), 319–346. https://doi.org/10.1080/17419166.2023.2164924

Osasona, T. (2023). The question of definition: Armed banditry in Nigeria’s north-west in the context of international human rights law. International Review of the Red Cross, 105(1), 735–749. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1816383122000457

Oyeleye, S. A. (2025). Emerging conflicts in Nigeria and Sahel region: Professionalism and challenges of media reportage. In A. Adeniyi, P. A. Obi, S. K. Usman, & I. U. Yusuf (Eds.), Media, conflicts and the national security question (pp. 145–161). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-82198-1_8

Renoir, M., Kassimatis, S., Coulibaly, A., & Kotsiras, D. (2024). Whose peace? Prioritizing local perspectives to inform our understanding of peacebuilding effectiveness. In S. L. Connaughton & J. R. Linabary (Eds.), Are we making a difference? Global and local efforts to assess peacebuilding effectiveness (pp. 225–243). Rowman & Littlefield.

Schirch, L. (2013). Conflict assessment and peacebuilding planning: Toward a participatory approach to human security (1st ed.). Kumarian Press.

Sha, D. P. (2005). The politicisation of settler-native identities and ethno-religious conflicts in Jos, Central Nigeria. Stirling-Horden Publishers.

Tapscott R. (2021). Vigilantes and the state: Understanding violence through a security assemblages approach. Cambridge University Press.

Wagner, U., & Hewstone, M. (2012). Intergroup contact. In L. R. Tropp (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of intergroup conflict (pp. 393–406). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199747672.013.0012

Youth Initiative Against Violence and Human Rights Abuse (YIAVHA). (2024a). A systems analysis of violent conflict in Riyom LGA, Plateau State: Community participatory action research report. Youth Initiative Against Violence and Human Rights Abuse.

Youth Initiative Against Violence and Human Rights Abuse (YIAVHA). (2024b). Impact evaluation report of the implementation of the Building Bridges for Peace project. Youth Initiative Against Violence and Human Rights Abuse.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR(S)

The Youth Initiative Against Violence and Human Rights Abuse (YIAVHA) is a youth-led non-profit organisation founded in 2016 to promote peacebuilding, human rights, and inclusive governance in conflict-affected communities across Nigeria. Through innovative, evidence-based methods such as storytelling, interfaith collaboration, and community engagement, YIAVHA brings together Christian and Muslim youth to disrupt cycles of violence. The organisation has empowered over 5,700 young people through intergenerational dialogue, digital engagement, capacity building, development projects, and legal support for victims of human rights violations. In Plateau State, YIAVHA has successfully transformed conflict between farmers and herders into cooperation through joint farming initiatives, helping rebuild trust and livelihoods. Its intercultural and interreligious dialogue circles provide safe spaces for people from diverse backgrounds to share experiences, heal from trauma, and foster mutual understanding. YIAVHA also works to prevent election violence and amplify youth voices in governance, believing that young people are powerful agents of peace and social change.

Received: November 26, 2025

Accepted: July 04, 2025

Published: October 31, 2025

Citation:

Youth Initiative Against Violence And Human Rights Abuse (YIAVHA). (2025). From Conflict to Cooperation: A Community-led Approach to Farmer-Herder Peacebuilding in Riyom, Plateau State, Nigeria. SustainE, 3(1), 164–178. In A. Akinsemolu, A. Eimer, & S. Iqbal (Eds.), Bridging power and knowledge: Addressing global imbalances in knowledge systems for sustainable futures [Special issue]. https://doi.org/10.55366/suse.v3i1.8

Disclaimer: The opinions and statements expressed in this article are the author(s) sole responsibility and do not necessarily reflect the viewpoints of their affiliated organizations, the publisher, the hosted journal, the editors, or the reviewers. Furthermore, any product evaluated in this article or claims made by its manufacturer are not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Distributed under Creative Commons CC-BY 4.0