Abdulkarim Muhammad Mubarak 123 Babakano Abduljalal13 Dolapo Popoola4 & Shehu Sani Gaddafi15

1Department of Electrical Engineering, Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, Nigeria.

2Policy and Advocacy Lead, Commonwealth Sustainable Energy Transition Youth (CSETY).

3Protection, Control and Metering Department, Transmission Company of Nigeria.

4Independent Power Sector Consultant, Liebe Solutions, Nigeria.

5Ministry of Power and Renewable Energy, Kano state, Nigeria.

*Corresponding Author Email: abdulkarim.muhammad@tcn.org.ng …

Highlights

- Advocates policy-driven solar deployment to harmonise energy access, affordability, and sustainability in rural Nigeria.

- Highlights decentralised solar systems as practical solutions to grid constraints and rural electrification gaps.

- Shows how financing models and energy management practices can improve scalability and affordability.

- Calls for targeted policy and institutional reforms to accelerate SDG 7 and climate action outcomes.

Abstract

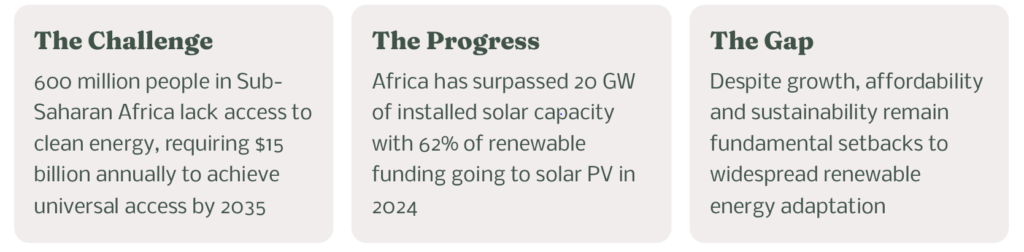

Renewable clean energy has emerged over the years as a favored approach to addressing energy shortage and environmental challenges through a series of climate action tied to sustainability goals and other global frameworks like SDG7. The International Energy Agency projects that renewable Energy will successfully harness resources and funding towards its research and development estimating $15 billion dollars yearly to achieve universal access by 2030 primarily to improve clean energy access for heating/cooling, cooking, transportation, building, lighting and industries in a coordinated effort to limit global temperatures to 1.5°C, conforming to the Paris agreement. Lack of sustainability and affordability form the fundamental setback preventing the widespread adaptation of Renewable energy technologies, it is thereby crucial to examine if the policies and framework guiding renewable energy adaptation are efficient. This research aims to deep dive into the policy, planning and energy management aspect of solar renewable energy in Nigeria. This research investigates the effectiveness of existing policies and management strategies, highlighting how they can be improved for unifying affordability of decentralized solar energy systems, solar energy mix and energy efficiency paired with informed political strategy or government mechanisms to influence access and reduce carbon emissions. Furthermore, this research will utilize case studies from other countries such as India, Egypt, China and Germany energy management techniques to analyze deployment issues such as energy efficiency, storage and financial models. Using a mixed methodology of data analysis from three case studies in Abuja, KAPSCO in Kaduna and University of Abuja to investigate the impact of solar renewable energy deployment in stimulating economic growth in hosting communities, finally in this research energy policies and their reforms are discussed towards contributing constructively to the improvement of the Nigerian energy sector and sustainable recommendations are proposed.

Keywords: Energy Financing, Solar Renewable Energy, Energy Policy, Sustainability, Affordability, Reduced Carbon Emissions, SDG 7, Rural Electrification Development, Energy Access

1. Introduction

This section gives a brief contextual background to this research work relating to regional advantage, acceptability, and adaptability of solar renewable energy. It also gives an insight into how global politics and local policies can influence the affordability of and access to solar renewable energy. With approximately 600 million people lacking access to clean energy, Sub-Saharan Africa faces significant challenges in achieving universal electricity access. The International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates that $15 billion per year is needed to achieve universal access by 2035 (International Energy Agency, 2025). To adequately address these challenges, the region requires a coordinated policy and planning effort to increase investment in electricity infrastructure, improve the commercial viability of projects, and develop innovative financing mechanisms. Sub-Saharan Africa is experiencing a significant surge in solar energy adoption, driven by the region’s abundant solar resources and declining photovoltaic costs. Recent industry data indicate that Africa has surpassed 20 GW of installed solar capacity across utility-scale, commercial, and off-grid segments (Africa Solar Industry Association [AFSIA], 2025). In parallel, distributed solar systems are rapidly expanding in several countries. In South Africa, Namibia, and Eswatini, distributed solar capacity has reached approximately 10% of national grid supply capacity, while year-on-year growth rates exceeding 40% have been recorded in Kenya, Eswatini, and Namibia, reflecting strong market-driven adoption in the absence of large subsidies (Thurber et al., 2025). Another interesting indicator is in investment trends where Solar PV dominates Africa’s renewable energy investments, accounting for 62% of total renewable funding in 2024, with utility-scale installations making up 40% and distributed installations accounting for 22% (Onyango, 2024; ESI Africa, 2025). Although a significant reversal in progress has been recorded due to the COVID-19 pandemic and, more recently, the Russian-Ukraine war.

Global politics and policies have always played a major role in influencing key aspects of climate action, as is evident in the varying levels of commitment to reducing greenhouse gas emissions among countries. The United Nations’ climate change secretariat has forecast a 10% cut in global emissions by 2035, but this falls short of the 60% reduction needed to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial temperatures (Abnett, 2025). To strengthen policy relevance, incorporating the Paris Agreement’s Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), which was adopted by 196 countries in 2015, aiming to limit global warming to well below 2°C of pre-industrial levels, is a great place to start. This has not yet yielded the much-anticipated results, as countries continue to default on political grounds.

Another example of a global mechanism is the global methane pledge, which aims to reduce methane emissions by 30% by 2030. Signed by over 150 countries, this pledge recognises the critical role methane reduction plays in mitigating the effects of climate change. However, this is also influenced by global politics. Heavy financiers such as China, Germany, France, and the USA always compete and try to outmatch each other, and when one country reduces funding abruptly, it triggers a cascading effect globally (United Nations Environment Programme, 2023; International Energy Agency, 2024).

There is a significant gap in policy coordination for Nigerian rural areas to take advantage of resources such as vast land and rivers to attract significant renewable energy investments. These investments would provide host communities with benefits such as improved access to clean and reliable electricity, stimulated economic activities, and generally improved well-being. A well-designed framework for policy design and implementation in renewable energy deployment will amplify efforts to reconcile bottlenecks such as costs, trade-offs, and harmonisation among the three objectives of energy security, climate change prevention and mitigation, and job creation (Timilsina et al., 2012), which this research aims to address.

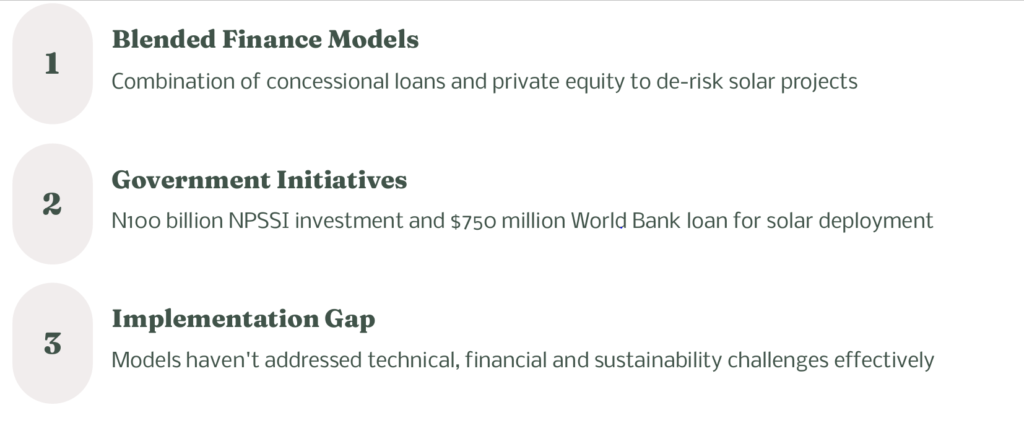

Previously, Nigeria has deployed several financial models to proliferate solar rural electrification, such as Blended Finance, which is a combination of concessional loans and private equity. Other models include results-based financing, pay-as-you-go, and minimum subsidy tender. Examples include the Nigeria Electrification Project, which has provided grants to de-risk solar projects, and the $750 million loan provided to Nigeria to support private solar project developers (Nigeria Electrification Programme, 2024; World Bank, 2023). Government efforts, such as the National Public Sector Solarisation Initiative (NPSSI) providing about N100 billion in investments to power public infrastructure with solar, in addition to creating an enabling environment and partnerships with the private sector, have also contributed immensely to the deployment of solar for rural electrification (Punch NG, 2025). The models adopted have not been robust enough to tackle technical, financial, and even sustainability issues, making it difficult to scale adaptability while trying to resolve access and affordability constraints. This further amplifies the urgent need for a change of perspective in the approach to rural electrification development policy in Nigeria: a model that is place-based and leverages local resources rather than previous models that emphasise centralisation and subsidies, thereby discouraging the competitiveness of rural areas (Ogbodo-Nathaniel et al., 2024).

Integrating the Nigerian renewable energy sector to participate competitively in the global supply chain will significantly impact harmonising access and affordability in local economies such as agriculture, forestry, traditional manufacturing, and green tourism, thus translating into development. However, there is a huge problem that hinders all this potential, namely, the problem of effective planning and policy to address affordability and sustainability issues (Ugwu & Adewusi, 2024). In harnessing all this potential for clean energy, especially in rural areas, we must find a way to unify accessibility and affordability through policy, planning, and energy management.

2. Review of Similar Works

This work showcases the use of PESTEL and SWOT analytic tools in analysing the impact of renewable energy development in Togo (Kansongue et al., 2023). It proposes using these tools to diagnose renewable energy implementation issues and to propose viable sustainable solutions. This approach could be beneficial for analysing Nigeria’s renewable energy governance structure and making adjustments, as there is currently a gap in understanding why existing policies are inadequate. According to the Clean Energy States Alliance (CESA, 2019) centre’s published report, in partnership with strategic stakeholders, on solar energy’s role in under-resourced communities, while identifying the most equitable and impactful strategies for advancing the proliferation of solar technologies, it underscores some key recommendations to achieving this:

- Minimising financial risks for low and moderate-income households to improve their confidence in utilising such technologies.

- Leveraging relationships and partnerships with trusted community organisations that have already built trust with community members.

- Expanding the financing options base.

- Improving service delivery and consumer experience to ensure maximum utilisation.

The limitations of this work in the Nigerian context are that financial risks are still high for developers, a breach of trust between communities, government, and partners persists, informal sectors are largely neglected, and huge regulatory gaps remain. Terawatt Solar (2023) explores how Ontario’s existing policies and programmes impact solar energy inclusion in achieving affordable housing when put in a socio-political context. In the Nigerian context, there are no policies directly addressing estate developers incorporating solar in homes, but incentives and rebates are potential avenues to explore, as seen to yield promising results in Ontario.

In its article publication “Solar-based solutions improving livelihoods in rural areas”, the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA, 2018) explores the possibilities of adopting solar-based technologies in rural agriculture and manufacturing. There is a technical gap that has hindered the facilitation of this process in Nigeria, in addition to the fact that informal sectors are not captured during planning. The absence of skilled labour to carry out maintenance services in rural areas, and the lack of easy access to spare parts due to zero local production, further worsens this situation. Solar energy has been widely recognised as a key enabler of socio-economic development, supporting education, small businesses, and household electricity access through innovative financing mechanisms such as pay-as-you-go (PAYG) solar models (World Bank, 2020).

In Nigeria, although PAYG solar systems have been deployed in small residential settings, their expansion beyond individual households has been limited, with challenges related to affordability, weak financing structures, and institutional constraints hindering scalability to community-level applications.

Evidence from the literature further suggests that inadequate attention has been given to the policy and planning dimensions of solar renewable energy development in Nigeria. While several national renewable energy policies exist, they often lack sufficient detail on long-term sustainability, affordability, and implementation mechanisms, resulting in fragmented and low-impact outcomes (IRENA, 2022). Addressing this policy and planning gap is critical to accelerating solar energy deployment in rural areas, with implications for reducing carbon emissions, stimulating local economic activities, and improving the quality of life through enhanced electricity access.

3. Methodology

The methodology of this research is heavily based on mixed-method data analysis. Data will be sourced from reports, articles, and publications from reliable sources, as well as interviews with critical stakeholders.

3.1 Barriers to Large-Scale Off-Grid Solar Deployment in Nigeria

Solar energy is often seen as a promising solution to Nigeria’s energy crisis; however, the large-scale deployment of off-grid solar energy solutions has faced significant hurdles such as policy coordination gaps, funding constraints, and technical challenges, which have limited its effectiveness in driving rural economic development. According to the Rural Electrification Agency’s Nigeria Electrification Programme (NEP), addressing these challenges requires structured stakeholder engagement and systematic data gathering from existing mini-grid and off-grid projects implemented across the country (NEP – Rural Electrification Agency, n.d.; African Development Bank Group, 2025). Examining data from solar mini-grids in Abuja and Kaduna uncovers common issues in off-grid solar energy deployment for rural communities. Many projects have insufficient capacity due to high costs and inadequate technical designs, failing to meet local energy needs. Costs, on the other hand, are a major concern, as most homes and companies cannot financially support the expensive outlay, let alone the ongoing costs, despite the availability of subsidies (World Bank, 2023; African Development Bank Group, 2025).

Projects implemented by federal agencies such as the Rural Electrification Agency (REA) and sub-national governments like Kaduna State Power Supply Company (KAPSCO) suffer from insufficient funding, poor supply chain management, and a lack of a skilled workforce, leading to slow installation processes and recurrent faults. Similarly, low awareness and limited knowledge about solar solutions also play a role in the low adoption rate. To make off-grid solar energy viable in Nigeria, it is crucial to ensure adequate funding, design projects that align with community needs, improve affordability through subsidies, and build local capacity for installation and maintenance (International Energy Agency, 2023; Rural Electrification Agency, 2024).

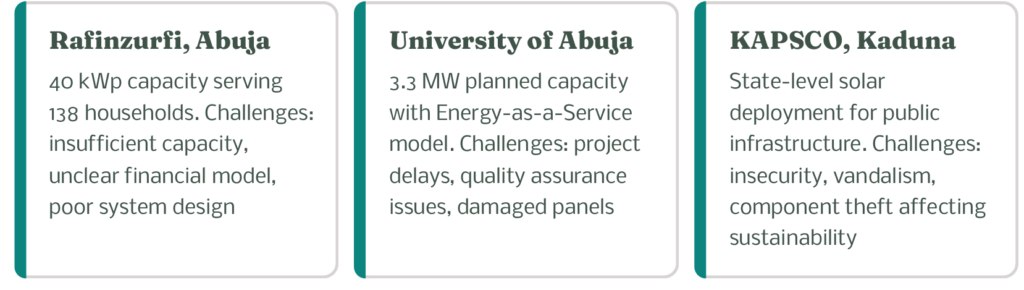

Case Study 1: Abuja Solar Mini-Grid Project

A solar hybrid mini-grid near Abuja, intended to power the Rafinzurfi rural community, initially promised to provide electricity to over 138 households, a community clinic, two schools, and 16 commercial users with a 40 kWp solar hybrid capacity; this is part of the REA pipeline funding to drive renewable projects across the country. However, due to the non-definition of electrification standards, community inhabitants have complained about limitations to what they are able to power in their homes. Due to insufficient installed capacity and poor system design, the project was unable to deliver reliable power to its initially intended audience, leading to community dissatisfaction and low adoption rates. The project’s high cost, both in terms of installation and ongoing maintenance, further exacerbated the issue, highlighting the need for better planning and more affordable solutions. Although the project has also recorded some wins in terms of stimulating economic activities in the community from extra hours gained for commerce due to lighting from streetlights powered by the project, there is no clear financial model that has been adopted for the consumers, leaving them at the mercy of developers (Odeyemi, 2024; World Bank, 2022).

Case Study 2: University of Abuja Solar Project

The University of Abuja Solar project, part of the World Bank’s Energizing Education Programme, is expected to provide 3.3 megawatts and 2 MWp of energy storage when completed, ensuring an uninterrupted power supply on campus. EMONE, as implementation partners, have proposed the Energy-as-a-Service business model where excess energy will be sold back to the grid, thereby ensuring sustainability through generating funds for maintenance and operations. After interviewing some students in the institution, they complained about the duration of the project’s completion, which the developers blamed on project management and funds disbursement. Another issue was quality assurance, as some of the panels installed were visibly already damaged even before the project’s completion (World Bank, 2024; Rural Electrification Agency, 2024).

Case Study 3: KAPSCO Solar Deployment in Kaduna

The Kaduna State Government, through initiatives involving the Kaduna State Power Supply Company (KAPSCO), has pursued solar energy deployment as part of broader efforts to improve infrastructure, service delivery, and economic activity across the state. The Kaduna State Development Plan (2021–2025) explicitly recognises energy access as a critical enabler of socio-economic development, including the deployment of renewable energy solutions for public infrastructure, markets, health facilities, and rural communities (Kaduna State Government, 2021). However, the wider operating environment for infrastructure projects in Kaduna State, particularly in rural areas, has been severely constrained by insecurity in north-western Nigeria.

Persistent violence, banditry, vandalism, and criminal activity have disrupted public services and infrastructure projects, increasing operational risks and maintenance costs while undermining investor confidence (International Crisis Group, 2023). These security challenges have direct implications for the sustainability of decentralised solar installations, including theft of components, damage to assets, and reduced system reliability. Despite these constraints, evidence from Kaduna’s development planning indicates that improved public lighting and electrification of markets and transport corridors have contributed to extended trading hours and enhanced economic activity in urban and peri-urban areas (Kaduna State Government, 2021). Such outcomes demonstrate the potential socio-economic benefits of solar deployment when projects are properly planned and protected.

3.2 Global Best Practices in Energy Reforms

Before attempting to apply the principles of energy reforms at a local level, one has to review the local policy documents and global case studies. This includes the manner in which various nations have addressed energy reforms, various strategies, and the results obtained. Based on this principle, local policy-makers are in a position to spot best practices in these frameworks that may be possibly implemented to address regional concerns. Engaging with key industry stakeholders, such as policy-makers, regulators, private developers, and investors, is also crucial. Through interviews and discussions, valuable insights can be gained about the challenges and opportunities in implementing energy reforms. Stakeholder engagement fosters collaboration, ensuring that reforms are well-informed and tailored to local contexts. It can therefore be seen that with adequate research and engagement with stakeholders, it is possible to be better placed in terms of formulating an effective approach to energy reform, one that will correspond with internationally accepted standards while at the same time meet regional requirements.

Case study 1: Germany’s Energiewende

Initiated in the early 2000s, Germany’s Energiewende is one of the most comprehensive energy reforms aimed at transitioning to a low-carbon, sustainable energy system. It focuses on expanding new sources of power generation, excluding nuclear energy, and enhancing energy efficiency. As of 2020, renewable energy accounted for nearly 45% of Germany’s electricity consumption, made possible through strong policy coherence addressing cross-cutting issues and active stakeholder engagement (European Commission, 2018; Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy, 2021).

Case Study 2: Denmark

Denmark has been a pioneer in integrating renewable energy, particularly wind power, into its national grid. The country has pursued long-term policies aimed at expanding renewable energy and improving system flexibility, enabling high levels of variable renewable energy integration. As a result, renewable energy accounts for more than half of Denmark’s electricity generation, with wind power playing a dominant role and solar power providing a growing contribution. Denmark has also set ambitious targets for transitioning to a fully renewable electricity and heating system (Agora Energiewende, 2022; Denmark.dk, n.d.).

Case Study 3: Egypt

Egypt faced a significant electricity supply deficit in the mid-2010s due to rapid population growth and increasing demand. In response, Egypt implemented power sector reforms and expanded generation capacity through large-scale infrastructure projects and international partnerships. These measures substantially increased installed electricity capacity and improved energy security, while recent renewable energy investments continue to support Egypt’s long-term energy transition objectives (Reuters, 2026; U.S. Energy Information Administration, 2024).

3.3 Policy Framework Analysis: PESTEL and SWOT Approaches

Here are some case studies and examples where PESTEL and SWOT analyses have been used to develop energy policies focussing on solar energy integration, enhancing access, and affordability:

Case Study 1: India’s and Iran’s Solar Energy Expansion

Overview: India’s strategic planning for solar energy expansion has been discussed in the literature using analytical frameworks such as PESTEL and SWOT to assess external macro-environmental factors and internal strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats that shape policy and deployment strategies in the renewable energy sector, including solar power development aimed at establishing India as a global leader in clean energy transition (Ministry of New and Renewable Energy, 2011).

PESTEL Analysis: Political: Strong government support through subsidies and incentives. Economic: Declining costs of solar panels and potential for job creation. Social: High public support for renewable energy due to pollution concerns. Technological: Rapid advancements in solar technology and manufacturing. Environmental: Need to reduce carbon emissions and dependence on coal. Legal: Implementation of favourable policies and regulations under the Electricity Act and other frameworks.

SWOT Analysis: Strengths: High solar irradiance, government support, and large land availability. Weaknesses: High initial investment costs and lack of local manufacturing capacity. Opportunities: Increasing foreign investment and potential for technological innovation. Threats: Policy instability and competition from other energy sources.

Outcome: These analyses helped Iran shape policies that facilitated a significant increase in solar capacity, aiming for 100 GW by 2022, and addressed key challenges like funding, infrastructure, and regulatory support (Molamohamadi, 2022).

Case Study 2: Germany’s Renewable Energy Policy

Overview: Germany’s Energiewende policy aims to transition the national energy system towards a low-carbon and sustainable model. The policy has been widely analysed using PESTEL and SWOT frameworks as analytical lenses to examine the political, economic, social, technological, environmental, and legal conditions shaping the transition, as well as the strengths and challenges of Germany’s energy system (Laes et al., 2014).

PESTEL Analysis: Political: Strong government commitment to renewable energy and phasing out nuclear power. Economic: High investment in renewable energy technologies, leading to job creation and economic growth in green industries. Social: Public support for renewable energy and environmental sustainability. Technological: Advances in renewable technologies and grid modernisation. Environmental: Goals to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and mitigate climate change. Legal: Implementation of feed-in tariffs and the Renewable Energy Sources Act (EEG).

SWOT Analysis: Strengths: Strong policy framework, robust grid infrastructure, and technological expertise. Weaknesses: High energy costs for consumers and industrial sectors. Opportunities: Export of renewable energy technologies and expertise. Threats: Grid stability issues due to intermittent renewable sources and opposition from traditional energy sectors.

Outcome: These strategic assessments have informed policy coordination and supported large-scale renewable energy integration, whilst also identifying persistent challenges related to infrastructure expansion, system flexibility, and cost distribution. Recent reviews indicate that Germany has achieved significant progress in renewable energy deployment but requires continued investment and policy alignment to meet future energy and climate targets (Zackariat et al., 2025).

Case Study 3: Kenya’s Renewable Energy Strategy

Overview: Kenya employed PESTEL and SWOT analyses to develop its energy strategy, particularly focusing on integrating renewable sources like solar and wind into its national grid to enhance energy access and affordability (Kansongue et al., 2023).

PESTEL Analysis: Political: Government initiatives to increase electrification and renewable energy uptake. Economic: Potential for economic development through increased energy access and reduced reliance on imported fuels. Social: High demand for reliable and affordable energy in rural areas. Technological: Need for investment in grid technology and off-grid solutions. Environmental: Efforts to reduce carbon footprint and promote sustainable development. Legal: Policies and regulations supporting renewable energy projects, including tax incentives and simplified licensing processes.

SWOT Analysis: Strengths: High renewable energy potential, particularly in solar and wind. Weaknesses: Limited grid infrastructure and technical expertise. Opportunities: Growth in green energy investment and technology transfer. Threats: Financial constraints and political instability.

Outcome: These analyses helped Kenya prioritise investments in renewable energy, improve policy frameworks, and attract international funding and partnerships, significantly increasing its renewable energy capacity and access (Kansongue et al., 2023).

In the following case studies, through the lens of PESTEL and SWOT analyses, these countries have demonstrated their active consideration of their internal and external environments, in order to establish policies aiming to integrate solar energy, improve energy accessibility, and affordability. From these analyses, policymakers can develop plans that focus on unique problems and capitalise on opportunities specific to those circumstances.

4. Nigerian Solar Energy Policy Landscape: Analysis and Implementation

4.1 Nigerian Electricity Act Amendment

In 1999, the new constitution was enacted which put electricity power under the exclusive list. This meant that the federal government had full and total control of the power industry (NESI) from the centre (National grid) and states or local governments could not generate, transmit or distribute their power autonomously. The 2005 electricity reform act saw the unbundling and privatisation of the defunct NEPA first to power holding company (PHCN) and then subsequently into 6 generation and 11 distribution companies, leaving the transmission company in government control in 2013. The 2023 amendment of the electricity act now puts the NESI on the concurrent list, which means that states now have the power to generate, transmit, and distribute their own electricity. The act also stipulates that at least 10% of generated power must be from renewable energy sources. Below is a SWOT analysis of these critical aspects of the act and how it affects renewable energy integration into the national grid and proliferation efforts.

Strengths: With this new amendment, states now have the freedom to generate, transmit, and distribute their own power, which allows for decentralisation and increased access with renewable energy sources like solar and mini-hydro.

Weaknesses: The states do not yet have a localised electricity/energy market to implement this amendment. Also, the issue of high capital for investment in network infrastructure presents a huge challenge.

Opportunities: There is huge potential in developing renewable energy resources such as solar; there is also huge potential for local and foreign investments to bridge the funding and infrastructural deficits.

Threats: There could be a policy rejection from interest groups who benefit from the pre-amendment status quo. There is a huge gap in technical skill, which threatens sustainability.

4.2 Vision 30 30 30

This is a strategy and framework being implemented by the federal government through the Ministry of Power to achieve 30 MW of power by 2030, with 30% renewable energy sources such as solar, hydro, and wind (Federal Government of Nigeria, 2015). This is a great initiative, but there are several bottlenecks that have hindered its success, such as lack of funding, failing R.E. projects due to technical and design defects, lack of government willpower, and policy inconsistencies.

4.3 Nigeria’s ETP

As a political and economic leader in the sub-Saharan Africa region, Nigeria is taking the lead in championing just and equitable climate action. Affected by several adverse effects such as desertification, flooding, pollution, etc. in different parts of the country, Nigeria is taking a bold step to improve the lives of its over 200 million citizens through economic development and climate action, hoping to achieve one of the world’s first true transitions. During COP26, the then-President Muhammadu Buhari announced Nigeria’s commitment to net-zero by 2060, which subsequently led to the unveiling of the ETP (Federal Government of Nigeria, 2022). The plan detailed what was required to achieve this commitment without compromising the country’s energy needs. Significant strides have been achieved, such as the passing of the Climate Change Act, which signifies government buy-in. An energy transition implementation working group and an energy transition office were also established to oversee the ETP (Federal Government of Nigeria, 2021; Federal Government of Nigeria, 2022).

Based on key insights such as the creation of job opportunities, the role of gas as a transition fuel, and investment opportunities, the ETP is a multi-pronged strategy which defines specific frameworks and timelines for emissions reduction across five main sectors: oil and gas, transportation, industry, cooking, and power. These sectors collectively account for about 65% of Nigeria’s emissions (Federal Government of Nigeria, 2022). The ETP has some specific core objectives that drive its implementation, such as driving economic growth by removing over 100 million people out of poverty, delivering access to renewable energy services for all, managing the expected long-term job losses in the oil sector due to transitioning, leading Africa’s first fair, inclusive, and equitable energy transition with gas as a transitional fuel, and finally streamlining all government-related energy transition initiatives (Federal Government of Nigeria, 2022).

4.4 Energy Mix

This refers to the diversity of methods for generating electricity. Nigeria operates a national grid system which is centralised and managed by the independent system operator of the Transmission Company of Nigeria, the only arm of the power sector that is still solely government-owned. After the privatisation of generation, Nigeria currently has about 27 generation plants, most of which are gas-powered and hydro-powered. Nigeria’s current energy mix for electricity generation is dominated by natural gas and hydropower, with only very limited contributions from other sources such as solar and diesel-based generation (Energy Sector Data, 2023). The question arises, what happens when there is a drop in water levels or a shortfall in gas supply, as we have seen in recent times? The answer is a drastic drop in generation capacity that leads to a drop in frequency, which in turn leads to grid collapse. Nigeria has experienced 24 grid collapses in the past six months alone (Nigerian Electricity Regulatory Commission, 2023). For a country that has abundant sunlight throughout the year, as well as good onshore and offshore wind, along with numerous other renewable/clean energy resources, the urgent need to diversify our energy mix arises to improve energy security, efficiency, and most importantly, to ensure there is access to reliable and affordable energy for all. This can be achieved through policy reforms, planning, and frameworks that will mandate a certain percentage of generated power to be from clean sources and also direct infrastructure and investment towards building the renewable energy sector to improve the Nigerian electricity generation energy mix.

4.5 Decentralisation

Many have argued that a centralised system has more limitations than advantages, especially concerning allowing states and regions to develop and utilise their localised resources in achieving energy security and independence using renewable energy sources, and also to improve access to unserved and underserved areas. Recently, the new Electricity Act was amended to allow states the individual autonomy to generate, transmit, and distribute power (Federal Government of Nigeria, 2023). This is a welcome development, as states such as Lagos, Enugu, Abia, Kaduna, and a few others who had an early start in positioning themselves strategically quickly took advantage of this policy reform to attract investments, thereby developing their respective state electricity markets. Some states have gone as far as having the national regulators (NERC) hand over regulatory duties to their state regulators, signifying how far their markets have developed (Aluko & Oyebode, 2024). This move is a classic example of how policies can be used to achieve decentralisation and its benefits, as many independent power providers have sprung up to dominate these markets.

4.6 Innovation

There is a need for incorporating technology and innovation to support policies that will help to harmonise access with affordability, as various challenges in the global renewable technology chain have continued to inhibit its proliferation (International Energy Agency, 2022). An example of such innovation is Project Noor, a digital solution that was developed during my fellowship with Student Energy. Student Energy is a global youth organisation that seeks to equip the next generation of energy leaders with the necessary tools and knowledge to lead the future of energy (Student Energy, 2023). The main objective of this solution is to leverage technology and data analytics to bridge the access gap between renewable/clean energy producers and consumers, such as unserved communities, homes, and businesses. Another objective of the platform is to serve as a reliable database for renewable energy statistics where it is deployed, to help track climate action and the amount of emissions removed or prevented by renewable energy projects. Finally, the platform’s key feature is incorporating different payment models for communities, homes, and businesses, thereby harmonising access with affordability. Innovations such as these are critical to supporting policy and planning for maximum impact.

4.7 Harmonising Access with Affordability

In achieving this goal, we must draw examples from the success stories of other countries that have achieved this, such as the Renewable Purchase Obligation, which mandates utilities to patronise a fixed percentage of renewable energy sources, or the National Solar Mission, targeting 100GW of solar by 2022, launched in 2014 in India. Another example is China’s Belt and Road Initiative, funded by Chinese and Asian banks in an attempt to reduce the global costs of renewable energy technology through overseas investments in partner projects. A key takeaway is building sustainable financial models that will suit our Nigerian context. One example is a policy we developed during my time as a Kashim Ibrahim Fellow and a Special Assistant to former Governor El-Rufai in Kaduna State. Our goal at the Kaduna Power Supply Company (KAPSCO) was to improve access to solar renewable energy in the state. After our research and assessments, we decided to develop a policy that would allow civil servants in the state to access different capacities of solar energy based on their levels and number of service years left, for either their homes, businesses, or farms. This was the first of its kind in Nigeria, a giant stride by a sub-national government to take the initiative in improving access to renewable and clean energy (Kaduna Electricity Distribution Company, 2021, 2024).

5. General Analysis

It can be argued that of all the policies that have been implemented in Nigeria to address solar renewable energy access and affordability thus far, a major problem is implementation. There is a serious gap in the methodology for implementing these policies, which further exposes the lack of a long-term vision for the renewable energy sector. Furthermore, the gap extends to technical inefficiencies such as project life cycle management, maintenance and operations, efficiency and storage, etc., and most importantly, these all contribute to the access and affordability of solar renewable energy.

6. Policy Recommendations

To achieve great success in the proliferation of solar renewable energy, the proposed policies must be hinged on renewable portfolio standards, research and development, and economic signals.

6.1 Technical

- Reduction of import duty for key essential components for the production of solar energy equipment.

- A database specifically for solar energy deployment should be developed to help track information pertaining to solar technology for planning, policy, and other purposes.

- Redefinition and standardisation of the term “electrification” to provide a clear path as to how renewable energy projects impact development and the standard of living.

- Coordination of all solar renewable energy efforts to manage duplicated efforts, ensure efficiency, sustainability, and manage failures.

- Invest in research and development to ensure local manufacturing of parts, develop improved quality of solar equipment, and reduce costs.

6.2 Financial

- Developing a funding pool specifically for Solar R.E deployment for on-grid and off-grid, which will be funded by the private sector, government, partners, and other creative sources such as “loss and damage funds”, “carbon finance”, etc.

- Debt relief in exchange for implementing R.E solar projects in Global South countries, which could be implemented and monitored through mechanisms such as the Loss and Damage Fund and the Just Energy Transition Partnerships (JETPs).

- Less dependency on foreign aid to implement solar R.E projects, and greater dependency on internal (local) funding that is based on sustainable business models.

- Innovation in R.E financing, such as green bonds, and commercial banks funding renewable energy projects with government support to de-risk such investments.

- Tax relief for solar R.E companies and start-ups that have displayed significant prospects in providing access, value, and reducing carbon emissions.

6.3 Skills and Capacity Building

- Setting up solar technology clusters for the production, installation, and maintenance of solar equipment.

- Integrating Nigeria into the global chain for solar renewable energy through leveraging the production of key components and skilled labour.

- Leveraging Polytechnics, Universities, and other institutions of higher learning to train and retrain a network of skilled labour.

- Facilitating knowledge and technical skills exchange programmes to enhance the transfer of knowledge locally and internationally.

6.4 Infrastructural

- Investing in creating solar energy use clusters, such as free trade zones, that will utilise such energy for production and other industrial uses.

- Investment in building distribution networks to off-take solar energy projects.

- Acquiring strategically placed land for large-scale solar energy deployment.

Conclusion

It is clear through this research and simulation that policy and planning have a critical role to play in harmonising affordability and accessibility to proliferate access to solar energy to unserved and underserved areas, in improving our energy security by diversifying our energy mix, and in decentralising our power utility to be location- and resource-based, amongst other benefits. It is therefore important that policymakers are well-equipped with the necessary knowledge and tools, such as this research, to aid their decision-making processes. This research will contribute significantly to achieving a diagnostic understanding of why the mandates of renewable and rural development agencies are not being achieved at a desired level. Considering that the research will focus on the sustainability and affordability of solar energy delivery in underserved or unserved regions in Nigeria through planning and policy, its results will be critical for decision-making on strategy and policy formulation for solar energy implementation in Nigeria. It will also facilitate the development of frameworks, strategies, and policy documents for other sub-Saharan countries to emulate. Finally, this research will be a meaningful contribution to the literature on solar energy policy implementation and on integrating affordability and access into our educational institutions and industries.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

Abnett, K. (2025). Counties’ new climate plans to start cutting global emissions, U.N. says. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com

Africa Solar Industry Association. (2025, August 8). Symbolic milestone of 20 GWp installed capacity passed in Africa; excellent prospects for year to come with 14 GWp under construction. AFSIA. https://www.afsiasolar.com/symbolic-milestone-of-20-gwp-installed-capacity-passed-in-africa-excellent-prospects-for-year-to-come-with-14-gwp-under-construction/

African Development Bank Group. (2025). Implementation progress and results report: Nigeria electrification project. https://www.afdb.org/sites/default/files/documents/projects-and-operations/nigeria-_nigeria_electrification_project-_p-ng-f00-020-ipr-march_2025.pdf

Aluko & Oyebode. (2024). Nigerian electricity regulatory oversight transfer to state commissions. https://www.aluko-oyebode.com/insights/nigerian-electricity-regulatory-oversight-transfer-to-state-commissions/

Clean Energy States Alliance. (2019). States clean energy progress report. https://www.cesa.org/resource-library/

Energy Sector Data. (2023). Nigeria electricity generation mix: Predominantly gas and hydropower. energypedia.info. https://energypedia.info/wiki/Nigeria_Electricity_Sector

European Commission. (2018). Mission-oriented research and innovation policy: A case study of the German Energiewende. Publications Office of the European Union. https://commission.europa.eu/system/files/2018-02/mission_oriented_r_and_i_policies_case_study_report_energiewende-de.pdf

ESI Africa. (2025). $15 billion a year needed to reach universal electricity access in Africa. https://www.esi-africa.com

Federal Government of Nigeria. (2015). National renewable energy and energy efficiency policy (NREEEP). Federal Ministry of Power. https://faolex.fao.org/docs/pdf/nig218514.pdf

Federal Government of Nigeria. (2021). Climate Change Act, 2021. https://ngfrepository.org.ng:8443/jspui/bitstream/123456789/6359/1/Climate%20Change%20Act%2c%202021.pdf

Federal Government of Nigeria. (2022). Nigeria energy transition plan: Achieving net-zero emissions by 2060. Federal Republic of Nigeria. https://climate-laws.org/document/nigeria-energy-transition-plan_1d3f

Federal Republic of Nigeria. (2023). Electricity Act 2023. https://nemsa.gov.ng/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/ELECTRICITY-ACT-2023.pdf

Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy. (2021). Renewable energy sources in figures: National and international development. German Federal Government. https://energiewende.bundeswirtschaftsministerium.de/EWD/Redaktion/EN/Newsletter/2021/03/Meldung/direkt-answers-infographic.html

International Energy Agency. (2022). Digitalisation and energy. https://www.iea.org/reports/digitalisation-and-energy

International Energy Agency. (2023). Financing clean energy transitions in emerging and developing economies. https://www.iea.org/reports/financing-clean-energy-transitions-in-emerging-and-developing-economies

International Energy Agency. (2024). Countries have a major opportunity to turn methane pledges into action. https://www.iea.org/commentaries/countries-have-a-major-opportunity-to-turn-methane-pledges-into-action

International Energy Agency. (2025). Financing electricity access in Africa: Executive summary. IEA. https://www.iea.org/reports/financing-electricity-access-in-africa/executive-summary

International Renewable Energy Agency. (2025). Global landscape of energy transition finance. IRENA.

IRENA. (2018). Off-grid renewable energy solutions to improve livelihoods. https://www.irena.org/-/media/Files/IRENA/Agency/Publication/2018/Jan/IRENA_Off-grid_Improving_Livelihoods_2018.pdf?la=en&hash=59C9F62113324CAB2C0D990246C5673FB805595E

Kaduna Electricity Distribution Company. (2021). Kaduna Disco signed 2021 financial statements. https://kadunaelectric.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Kaduna-Disco-Signed-2021-FS.pdf

Kaduna Electricity Distribution Company. (2024). Q1 2024 performance report. https://kadunaelectric.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Q1_Report_2024_KE_V7.pdf

Kansongue, N., Njuguna, J., & Vertigans, S. (2023). A PESTEL and SWOT impact analysis on renewable energy development in Togo. Frontiers in Sustainability, 3, Article 990173. https://doi.org/10.3389/frsus.2022.990173

Laes, E., Gorissen, L., & Nevens, F. (2014). Governance challenges in the German energy transition. Sustainability, 6(3), 1129–1149. https://doi.org/10.3390/su6031129

Ministry of New and Renewable Energy. (2011). Strategic plan for new and renewable energy sector for the period 2011–2017. Government of India. https://rise.esmap.org/sites/default/files/library/india/India%20Strategic%20Plan%20for%20New%20and%20Renewable%20Energy%20Sector%20for%20the%20Period%202011-17.pdf

Molamohamadi, Z. (2022). Analysis of a proper strategy for solar energy deployment in Iran using SWOT-Matrix. Renewable Energy Research Applications, 71–78.

NEP – Rural Electrification Agency. (n.d.). Nigeria Electrification Programme. https://nep.rea.gov.ng/

Nigeria Electrification Programme. (2024). Nigeria Electrification Programme: Financing instruments and implementation approach. Rural Electrification Agency of Nigeria. https://nep.rea.gov.ng/

Nigerian Electricity Regulatory Commission. (2023). Fourth quarter 2023 NERC quarterly report: Electricity on demand. https://nerc.gov.ng/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/2023_Q4_Report_Final-1.pdf

Odeyemi, T. (2024). REA and Nayo Tropical Technology Limited have launched a 40 kWp solar hybrid mini-grid in Rafinzurfi community, Gwagwalada. The Electricity Hub. https://theelectricityhub.com/rea-and-nayo-tropical-technology-limited-have-launched-a-40kwp-solar-hybrid-mini-grid-in-rafinzurfi-community-gwagwalada/

Ogbodo-Nathaniel, P. A., Olujobi, O. J., & Monehin, V. B. (2024). An examination of the legal, policy, and institutional framework for promoting renewable energy projects as panaceas for sustainable development in Nigeria. Journal of Sustainable Development Law and Policy, 15(3), 64–90.

Onyango, A. (2024, November). Boom in renewable energy jobs but African countries lag behind—Report. The Eastleigh Voice.

Punch NG. (2025, August 8). FG to tackle energy cost in public institutions with N100 bn solar initiative. https://punchng.com/fg-to-tackle-energy-cost-in-public-institutions-with-n100bn-solar-initiative/

Student Energy. (2023). About Student Energy. https://studentenergy.org/about

Terawatt Solar. (2023, August 25). Exploring solar incentives and rebates in Ontario: A comprehensive guide. https://www.terawattsolar.ca/solar-incentives-in-ontario

Thurber, M. C., Nana, J., & Mutiso, R. (2025). No subsidies, no problem: The organic rise of distributed solar in sub-Saharan Africa. Energy for Growth Hub. https://energyforgrowth.org/article/no-subsidies-no-problem-the-organic-rise-of-distributed-solar-in-sub-saharan-africa/

Timilsina, G. R., Kurdgelashvili, L., & Narbel, P. A. (2012). Solar energy: Markets, economics and policies. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 16(1), 449–465. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2011.08.009

Ugwu, M. C., & Adewusi, A. O. (2024). Impact of financial markets on clean energy investment: A comparative analysis of the United States and Nigeria. International Journal of Scholarly Research in Multidisciplinary Studies, 4(2), 8–24.

United Nations Environment Programme. (2023). The global methane pledge: Fast action on methane to keep a 1.5°C future within reach. UNEP. https://www.unep.org/explore-topics/climate-action/what-we-do/global-methane-pledge

World Bank. (2020). Off-grid solar market trends report 2020: Lighting global homes. World Bank Group. https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/energy/publication/off-grid-solar-market-trends-report-2020

World Bank. (2023, December 15). Nigeria to expand access to clean energy for 17.5 million people [Press release]. https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2023/12/15/nigeria-to-expand-access-to-clean-energy-for-17-5-million-people

World Bank. (2024). Energising Education Programme (EEP): Project documents. https://projects.worldbank.org/en/projects-operations/project-detail/P161885

Zackariat, M., Hartz, K., & Huneke, F. (2025). The energy transition in Germany: State of play 2024—Review of key developments and outlook for 2025. Agora Energiewende. https://www.agora-energiewende.de/fileadmin/Projekte/2025/2024-18_DE_JAW24/2024-18_EN_JAW24_Presentation_250110.pdf

About this Article

Cite this Article

APA

Mubarak, A. M., Abduljalal, B., Popoola, D., & Gaddafi, S. S. (2026). Harmonising solar energy access and affordability in Nigeria: The role of policy and energy management in rural electrification. SustainE, 3(4), 1–18. doi:10.55366/suse.v3i4.3

Chicago

Abdulkarim Muhammad Mubarak, Babakano Abduljalal, Dolapo Popoola and Shehu Sani Gaddafi (2026). Harmonising solar energy access and affordability in Nigeria: The role of policy and energy management in rural electrification. SustainE. 1, no. 2 (January 22, 2026). 1-18. https://doi.org/10.55366/suse.v3i4.3

Received

13 August 2025

Accepted

16 December 2025

Published

22 January 2026

Corresponding Author Email: abdulkarim.muhammad@tcn.org.ng

Disclaimer: The opinions and statements expressed in this article are the authors’ sole responsibility and do not necessarily reflect the viewpoints of their affiliated organizations, the publisher, the hosted journal, the editors, or the reviewers. Furthermore, any product evaluated in this article or claims made by its manufacturer are not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Distributed under Creative Commons CC-BY 4.0

Share this article

Use the buttons below to share the article on desired platforms.