Akinterinwa E.T.;1 Oladejo B.O.;2 & Oladunmoye M.K.3

1Department of Microbiology, Federal University of Technology, Akure, PMB 704, Ondo State, Nigeria.

Corresponding Author Email:akinterinwatomilayo@yahoo.com

Abstract

Respiratory tract infections (RTIs) affect various components of the respiratory system—including the lungs, trachea, pleural cavity, bronchi, upper respiratory tract, and the associated muscles and nerves—either individually or in combination. The most dangerous and fatal of these infections are typically of bacterial aetiology. Bacteria such as Streptococcus pneumoniae, Streptococcus pyogenes, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Moraxella catarrhalis, Staphylococcus aureus, Haemophilus influenzae, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis are commonly implicated. Clinical manifestations include sinusitis, rhinitis, otitis, tonsillitis, epiglottitis, laryngitis, bronchitis, and pneumonia. The efficacy of conventional antibiotics (e.g., ampicillin, erythromycin, amoxicillin, and penicillin) is diminishing due to the emergence of antimicrobial resistance. Consequently, there is an urgent need to explore alternative treatment options to manage these infections effectively.

Keywords: Respiratory tract infections, bacterial aetiology, clinical manifestations, antimicrobial resistance, alternative treatment options.

1. Introduction

The human respiratory system is essential for the vital exchange of gases, supplying the body with oxygen and eliminating carbon dioxide. Without this gaseous exchange, life cannot be sustained. Anatomically, the respiratory system is divided into two primary sections:

- Upper Respiratory Tract (URT): This section, which includes the nose, epiglottis, sinuses, pharynx, and larynx, protects the lower respiratory regions from external harm while facilitating airflow (Thomas, 2013).

- Lower Respiratory Tract (LRT): The site of gas exchange, comprising the lungs, trachea, and bronchi (Weibel, Sapoval, & Filoche, 2005).

The human body is in constant interaction with millions of microbes during everyday activities such as breathing. Accordingly, RTIs encompass illnesses that affect various structures of the respiratory system (Ahmed et al. 2022). Although the majority of RTIs are viral in origin, bacterial infections can be exceptionally dangerous and even lethal. The URT plays a crucial role in filtering, heating, and humidifying air prior to its entry into the lungs (Santacroce et al. 2020). Numerous bacterial genera—including those within the phyla Firmicutes, Actinobacteria, Bacteroidetes, Proteobacteria, and Fusobacteria—inhabit the mucosal surfaces of the URT (Sahin-Yilmaz & Naclerio, 2011; Campanella et al. 2018; Finlay & Finlay, 2019). Although nasopharyngeal infections are common and associated with significant morbidity, infections of the LRT, while less frequent, tend to be more deadly. The bacteria colonising the nasal and oral cavities are often distinct in their niche specificity (Santacroce et al. 2020).

Globally, respiratory tract illnesses such as pneumonia, influenza, and tuberculosis accounted for approximately four million deaths in 2012 (World Health Organization [WHO], 2014). Notably, many members of the respiratory microbiota are opportunistic pathogens whose potential to cause disease is determined by their ability to evade the host’s immune defences as seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1: The Human Respiratory System. Source: Cancer Council NSW, 2024

2. Types of Bacterial Infections of the Human Respiratory Tract (BIHRT)

Respiratory infections are typically classified according to the site of infection, with the suffix “–itis” denoting inflammation. These Classifications include;

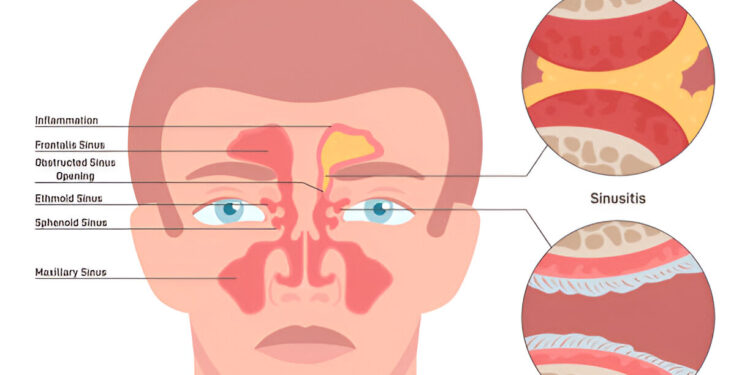

- Sinusitis: Inflammation of the sinuses. Bacterial agents implicated in sinusitis include S. pneumoniae, Moraxella catarrhalis, and H. influenzae (Grief, 2013).

- Rhinitis: Inflammation of the nasal cavities, commonly known as the common cold. The principal causative agents include S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae, and M. catarrhalis.

- Otitis: Inflammation of the ear. Acute otitis media is characterised by the accumulation of pus in the middle ear, leading to otalgia (ear discomfort), tympanic membrane bulging, and often systemic symptoms such as fever, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhoea, particularly in infants. Bacteria associated with acute otitis media include Escherichia coli, Enterococcus species, S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae, and M. catarrhalis.

- Tonsillitis: Inflammation of the tonsils, most commonly caused by Streptococcus pyogenes, Staphylococcus aureus, S. pneumoniae, and H. influenzae (Bartlett, Bola, & Williams, 2015).

- Epiglottitis: Inflammation of the epiglottis. Causative agents include H. influenzae serotype b, other serotypes (A and F) as well as non-typeable strains, S. pyogenes, and S. aureus (Bower, McBride, & Mandell, 2015; Blot et al. 2017; Tristram, 2018).

- Laryngitis: Inflammation of the larynx, primarily associated with M. catarrhalis and H. influenzae (Caserta & Mandell, 2015).

- Bronchitis: Inflammation of the bronchial tubes.

- Pneumonia: The most severe form of RTI, involving infection and inflammation of the lung alveoli. Pneumonia impairs gas exchange, often producing a productive cough with mucus and phlegm. Although pneumonia may have viral, fungal, or bacterial origins, bacterial pneumonia is most common, with S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae, and Mycoplasma pneumoniae being the principal agents (Segal, Weiden, & Horowitz, 2015).

3. Diagnosis of Bacterial Infections of the Human Respiratory Tract (BIHRT)

Diagnosis of BIHRT is primarily based on clinical signs and symptoms. Laboratory diagnosis typically involves culture-based identification techniques to isolate and identify the specific bacterial pathogen from samples collected at the site of infection. Advances in polymerase chain reaction (PCR) methodologies and serological techniques have further enhanced the accuracy and speed of pathogen identification.

4. Treatment of Bacterial Infections of the Human Respiratory Tract (BIHRT)

The treatment of bacterial RTIs commonly involves the administration of antibiotics such as amoxicillin in combination with β-lactamase inhibitors, macrolides, and cephalosporins—which are noted for their efficacy and tolerability in conditions such as chronic bronchitis and pneumonia (Vogel, 1995). Additional examples of antibiotics used in clinical practice include tetracycline, erythromycin, chloramphenicol, gentamycin, and various β-lactam antibiotics. For an antibiotic to be effective against bacteria, three conditions must be met: the antibiotic must reach the target in sufficient concentration, a receptive target must be present in the bacterial cell, and the antibiotic must not be inactivated or altered.

Antibiotics typically exert their effects via one of the following five mechanisms:

- Inhibition of Protein Synthesis: Macrolides, for example, bind to the 50S ribosomal subunit and impede the elongation of nascent polypeptide chains.

- Interference with Cell Wall Synthesis: β-lactam antibiotics, such as penicillins and cephalosporins, inhibit enzymes critical to the synthesis of the peptidoglycan layer (Benton et al. 2007).

- Inhibition of Metabolic Pathways: Agents such as trimethoprim and sulphonamides (e.g., sulfamethoxazole) block steps in folate synthesis, a cofactor in nucleotide biosynthesis (Strohl, 1997).

- Interference with Nucleic Acid Synthesis: Rifampicin acts by obstructing DNA-directed RNA polymerase.

- Disruption of Cell Membrane Integrity: Certain antibiotics target the inner membrane of Gram-negative bacteria or the cytoplasmic membrane of Gram-positive bacteria.

Despite these strategies, the global efficacy of antibiotics is declining. This decline is attributable to several factors, including the high cost and limited availability of certain drugs, as well as the rapid emergence of bacterial resistance. Resistance is often mediated by the horizontal transfer of mobile genetic elements via plasmids (Bennett, 2009) and is exacerbated by the overuse and misuse of antibiotics. Additionally, the formation of biofilms through quorum-sensing mechanisms can lead to the release of β-lactamases, which degrade a range of antibiotics (Wilke, Lovering, & Strynadka, 2005). Reports indicate resistance among common pathogens, with S. pneumoniae showing resistance to both penicillin and erythromycin, H. influenzae exhibiting resistance to ampicillin, and S. pyogenes isolates resistant to erythromycin (Karchmer, 2004).

5. Conclusion

Bacterial infections of the respiratory tract represent a significant health risk, particularly when not managed appropriately. Key pathogens—including Streptococcus pneumoniae, Streptococcus pyogenes, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Moraxella catarrhalis, Haemophilus influenzae, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and Staphylococcus aureus—are becoming increasingly resistant to conventional antibiotics. This situation necessitates the exploration of alternative treatment strategies to manage RTIs effectively and to mitigate the global challenge of antibacterial resistance.

References

Ahmed, N., Habib, S., Muzzammil, M., Rabaan, A. A., Turkistani, S. A., Garout, M., Halwani, M. A., Aljeldah, M., Al Shammari, B. R., & Sabour, A. A. (2022). Prevalence of bacterial pathogens among symptomatic‐SARS‐CoV‐2 PCR‐negative patients. Microorganisms, 10, 1978.

Bartlett, A., Bola, S., & Williams, R. (2015). Acute tonsillitis and its complications: An overview. Journal of the Royal Naval Medical Service, 101, 69–73. https://doi.org/10.1136/jrnms-101-69

Bennett, P. M. (2009). Plasmid encoded antibiotic resistance: Acquisition and transfer of antibiotic resistance genes in bacteria. British Journal of Pharmacology, 153, S347–S357.

Benton, B., Breukink, E., Visscher, I., Debabov, D., Lunde, C., Janc, J., Mammen, M., & Humphrey, P. (2007). Telavancin inhibits peptidoglycan biosynthesis through preferential targeting of transglycosylation: Evidence for a multivalent interaction between telavancin and lipid II. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents, 29, 51–52.

Blot, M., Bonniaud-Blot, P., Favrolt, N., Bonniaud, P., Chavanet, P., & Piroth, L. (2017). Update on childhood and adult infectious tracheitis. Médecine et Maladies Infectieuses, 47, 443–452. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medmal.2016.06.006

Bower, J., McBride, J., & Mandell, T. (2015). Douglas, & Bennett’s principles and practice of infectious diseases. In Croup in children (acute laryngotracheo-bronchitis) (pp. 762–766.e1). Elsevier.

Campanella, V., Syed, J., Santacroce, L., Saini, R., Ballini, A., & Inchingolo, F. (2018). Oral probiotics influence oral and respiratory tract infections in the paediatric population: A randomised double‐blinded placebo‐controlled pilot study. European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences, 22, 8034–8041.

Cancer Council NSW. (2024). About lung cancer. Cancer Council NSW. https://www.cancercouncil.com.au/lung-cancer/about-lung-cancer/

Caserta, M., & Mandell, T. (2015). Douglas, & Bennett’s principles and practice of infectious diseases. In Acute laryngitis (pp. 760–761). Elsevier.

Finlay, B. B., & Finlay, J. M. (2019). The whole-body microbiome: How to harness microbes—inside and out—for lifelong health (1st ed., pp. 238–260). The Experiment.

Grief, S. N. (2013). Upper respiratory infections. Primary Care, 40, 757–770. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.pop.2006.04.004

Karchmer, A. W. (2004). Increased antibiotic resistance in respiratory tract pathogens: PROTEKT US—an update. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 39, S142–S150.

Sahin-Yilmaz, A., & Naclerio, R. M. (2011). Anatomy and physiology of the upper airway. Proceedings of the American Thoracic Society, 8, 31–39.

About this Article

Cite this Article

APA

Akinterinwa E.T., Oladejo B.O. & Oladunmoye M.K. (2025). Bacterial Infections of the Human Respiratory Tract (BIHRT). In Akinyele B.J., Kayode R. & Akinsemolu A.A. (Eds.), Microbes, Mentorship, and Beyond: A Festschrift in Honour of Professor F.A. Akinyosoye. SustainE

Chicago

Akinterinwa E.T., Oladejo B.O. and Oladunmoye M.K. 2025. “Bacterial Infections of the Human Respiratory Tract (BIHRT)” In Microbes, Mentorship, and Beyond: A Festschrift in Honour of Professor F.A. Akinyosoye, edited by Akinyele B.J., Kayode R. and Akinsemolu A.A., SustainE.

Received

15 December 2024

Accepted

10 January 2025

Published

4 February 2025

Corresponding Author Email: akinterinwatomilayo@yahoo.com

Disclaimer: The opinions and statements expressed in this article are the authors’ sole responsibility and do not necessarily reflect the viewpoints of their affiliated organizations, the publisher, the hosted journal, the editors, or the reviewers. Furthermore, any product evaluated in this article or claims made by its manufacturer are not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Distributed under Creative Commons CC-BY 4.0

Share this article

Use the buttons below to share the article on desired platforms.